Into the Grooves with Vinylmania's Charlie Grappone

Inside the history of the taste-making Greenwich Village store that offered gotta-have tunes and a safe space for music obsessives across four decades.

I’m a huge Madonna collector, but — though I have long argued her primary appeal is forever the music — I gave up on collecting her work on vinyl years ago,

The reason has nothing to do with a lack of affection for the stuff and everything to do with how much it broke my heart when the recording industry abruptly moved away from vinyl with the advent of the too-perfect CD, which came in a tiny jewel case with microscopic art compared to the bold 12" x 12" imagery to which I'd become addicted.

Even now that vinyl has made a comeback, I feel guarded, but talking to Charlie Grappone is a reminder of just how potent not just music but records were back in the day, and back in the gay.

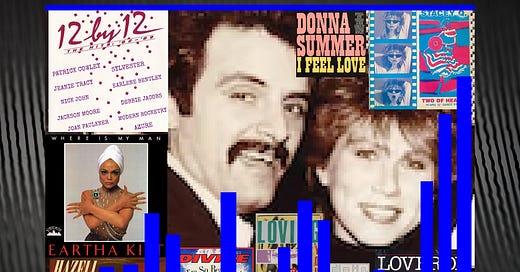

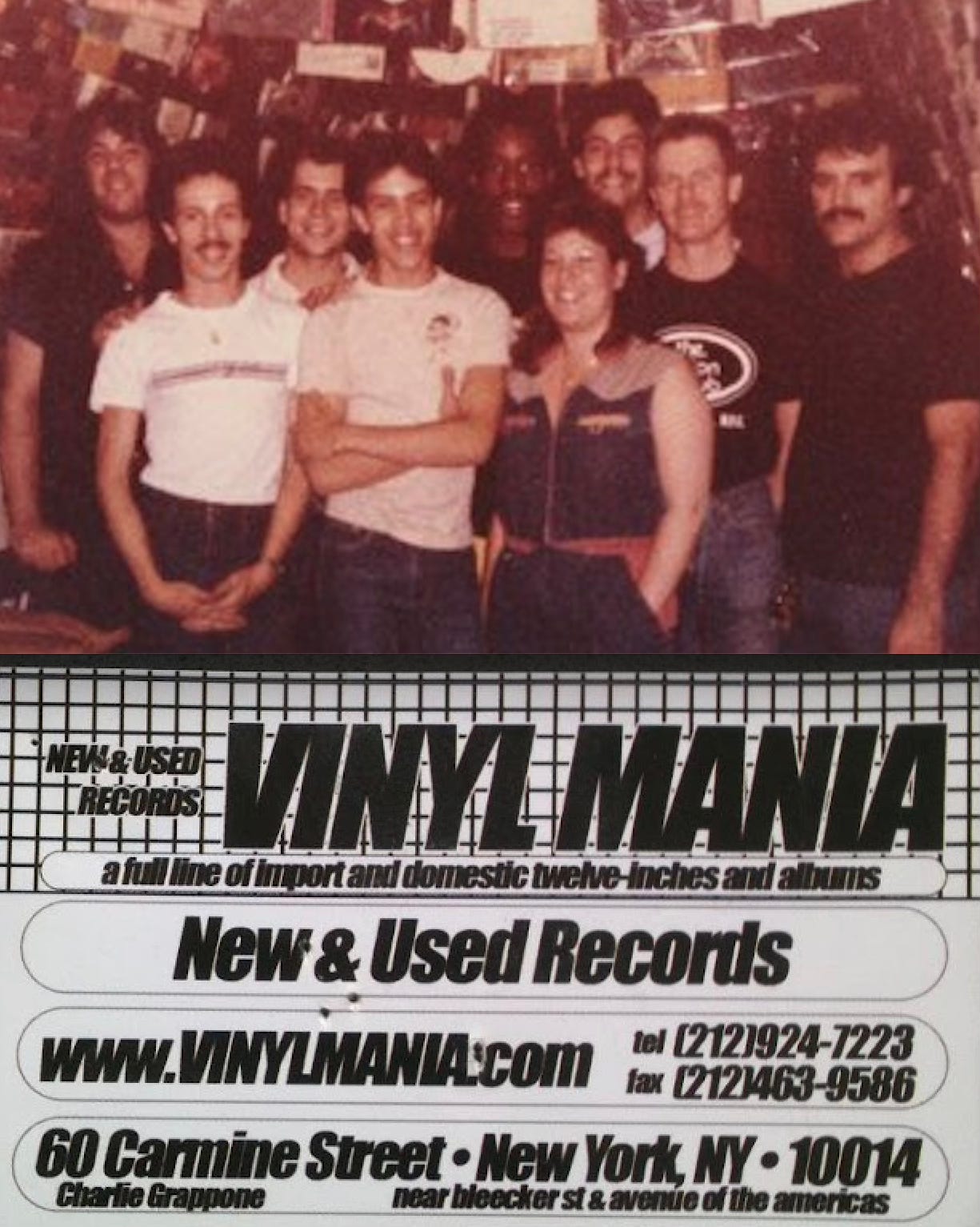

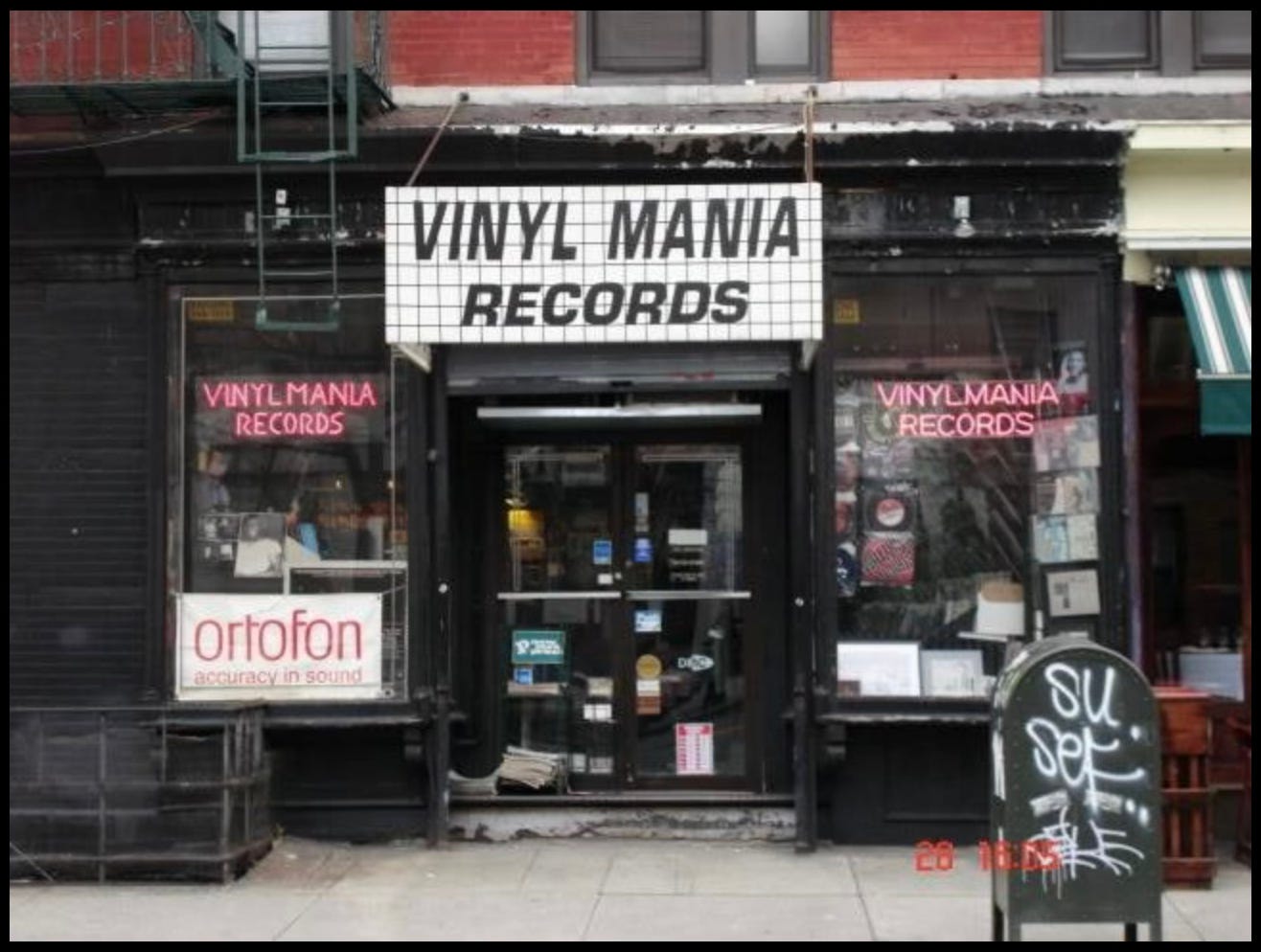

Grappone, with his wife Debbie, was the owner and operator of NYC's Vinylmania, a dance-music store at 30 Carmine St. in Greenwich Village that was among the first of its kind and one of the longest-lasting, a bastion of the latest tunes, the raddest sleeves and the addicts who hung out there chasing the perfect track.

“Charlie and Vinylmania were a very influential part of the NYC dance scene, well-known worldwide,” says John Pita, a friend of Charlie’s who owns and operates import nirvana Record Runner at 5 Jones St. “It was a must-stop for all DJs.”

Vinylmania was indispensable from the end of the Disco Era, 1978, right up to 2007, 29 years that saw the birth of HiNRG, the emergence and overwhelming impact of the AIDS pandemic and the advent of the Internet, all of which Charlie witnessed, and all of which affected both his business and his life.

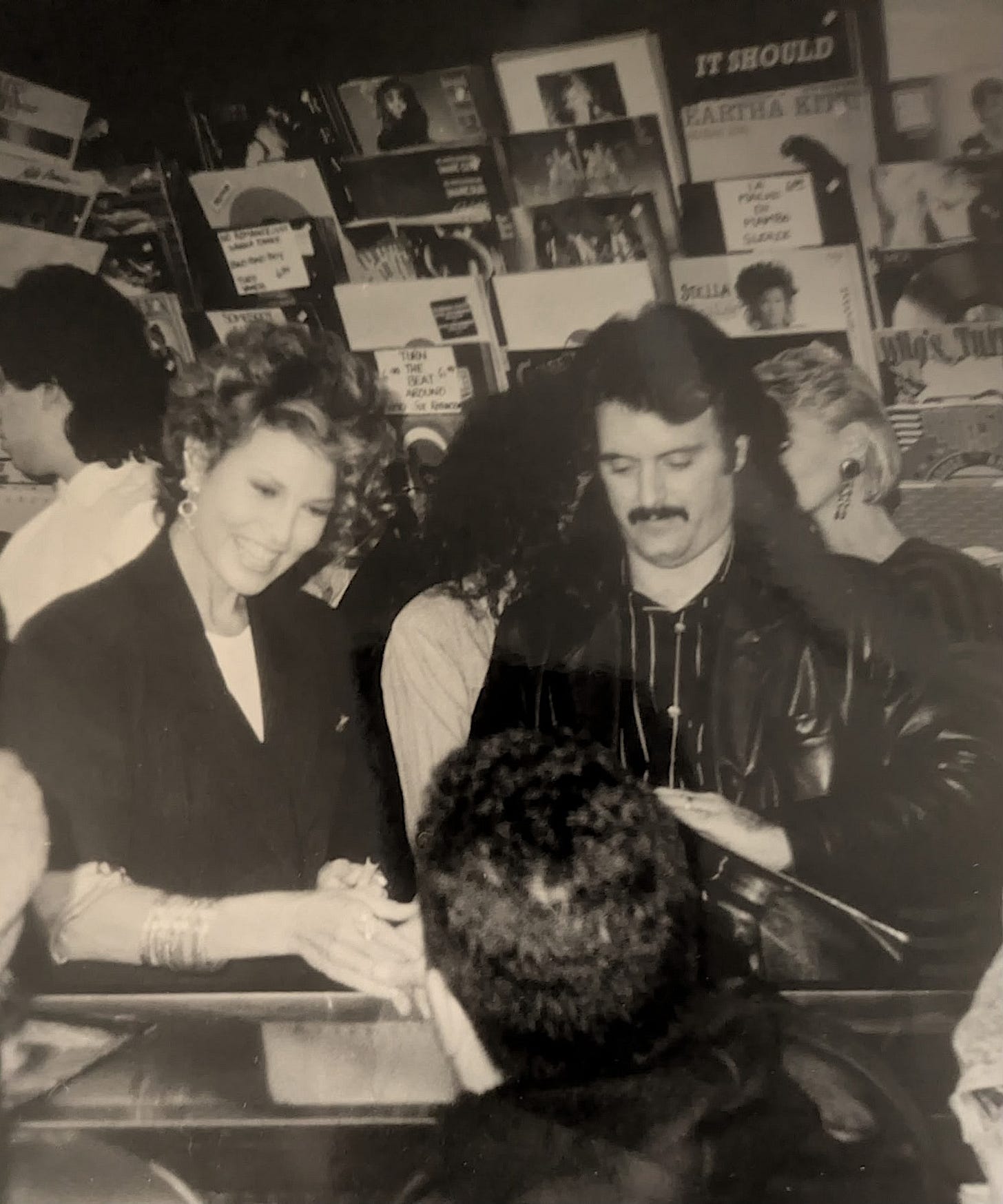

Of special interest to me, Charlie hosted Madonna's first-ever in-store signing way back in 1983. It was an afternoon few remember today, even though it took place at the dawn of one of rock's most illustrious careers.

I spoke with Charlie about the days when Vinylmania was the place for Manhattanite music buffs to get into groove.

Why did you decide to launch this particular business?

I was into records from 5 years old. I always collected it. During the '60s, with the British Invasion, I really got into it and started buying records seriously. If there was a group and someone in the group did a record, I'd have that offshoot. My friends used to get a kick out of it. I used to know catalogue numbers and stuff.

I started with 45s and then got into LPs. I had a nice collection. When I moved into Manhattan, I started making connections to get a lot of records. Then I decided to maybe turn the hobby into a little business.

Did you sell some of your original collection as part of your inventory?

Yes. There were a lot of stores in Greenwich Village at that time, and most of them were rock stores. I said, “Well, I have a lot of this stuff.” I started with 45s. I said, “Well, really, am I going to play these as much as I'm going to play LPs? No.” I put all my Beatles picture sleeves and Rolling Stones picture sleeves on the wall of the first store. It's not that it was hard to part with; I think sometimes you got to come to decisions, and records take up a lot of room.

Where did you get the name?

I just said, “I'm going to call it Vinylmania.” A lot of people have tried to copy it. Coca-Cola spends probably millions protecting their name in every country in the world. And when you're going to trademark something like that, that costs money, so I never really protected the name. I figured I wouldn't have to. But there was a store in Austria, a store up in Boston. Some would call and ask me, “Can I call my store Vinylmania?” I said, “You can't think of a better name?”

Was the selling of promotional records a relatively new concept at that point?

I don't think anyone did it before me like I did it. In other words, I didn't look into it with a lawyer, I just looked at it and said, “What does this mean? ‘Sale is unlawful.’ They're giving it away, yet they're telling you that you can't do anything with it? I said, “You know what? I'm going to give it a shot.”

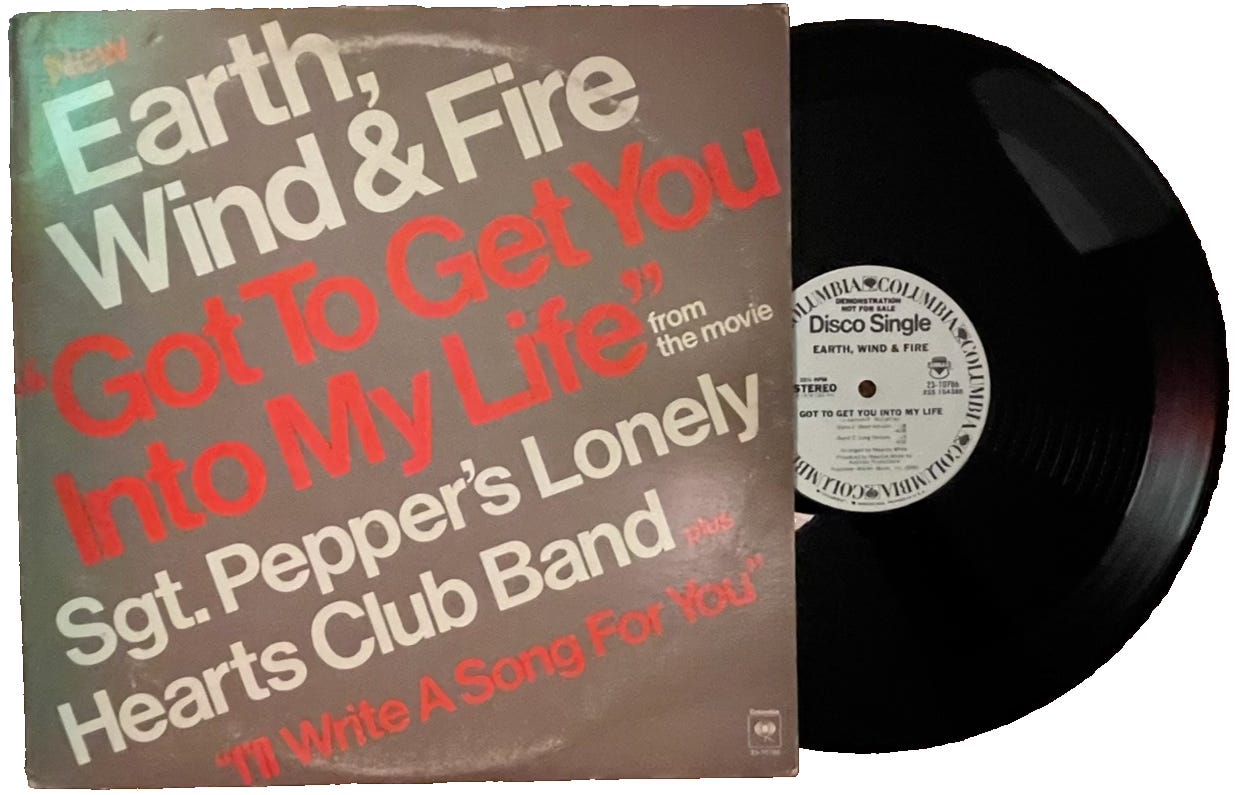

I was the superintendent of three buildings on 14th St., and John Pita [of Record Runner] moved into a building. I got him this duplex apartment. John had a 12-inch collection, and I had never seen anything like this. The first one he ever showed me was “promo-only” — it was Earth, Wind and Fire's cover of “Got to Get You into My Life” without a picture cover, but a worded cover. I was blown away. I said, “What the hell is this?” He explained it was “because you got to be a DJ. You got to be in a record pool to get that.” He taught me a lot about it. That's why in anything I ever do, interviews or magazines, I always tell them about John. My first promo contact was through him. There was a guy that used to come sell John promos, Kenny, a big, heavy-set guy. He had a glass eye, I'll never forget. He used to come in with two shopping bags full of promos.

One time, I said, “John, do you mind if I look at the records?” They were a dollar-fifty. I started buying from the guy. And then, after a while, I said to the guy, “How much for all of them?” He said, “They're a dollar-fifty, so 100 records is $150.” I said I'd take them all from then on. The guy started bringing records like crazy.

The only guy who was against me selling promos was Mel Cheren, who owned a label called West End [and helped found Paradise Garage]. He hated promos. Why? He said it was against the law. [Laughs] Where is it written down as a law? No one else ever came and said, “Hi, I'm from such and such. You're not supposed to be doing this.”

Had you always been friendly with your rival stores, like John's Record Runner and David Shebiro’s Rebel Rebel?

All the record store owners, like John and David of Rebel Rebel, I got along with everybody. I didn't look at it as a competitive thing at all. In the early '80s, there had to be 40 different stores between the East and West Village. All of these stores, there was a reggae store, a couple of dance music stores, rock store, heavy metal store, oldies. It was so diverse that it's not like you were stepping on anybody's toes.

My store was unique — the place to get 12-inches.

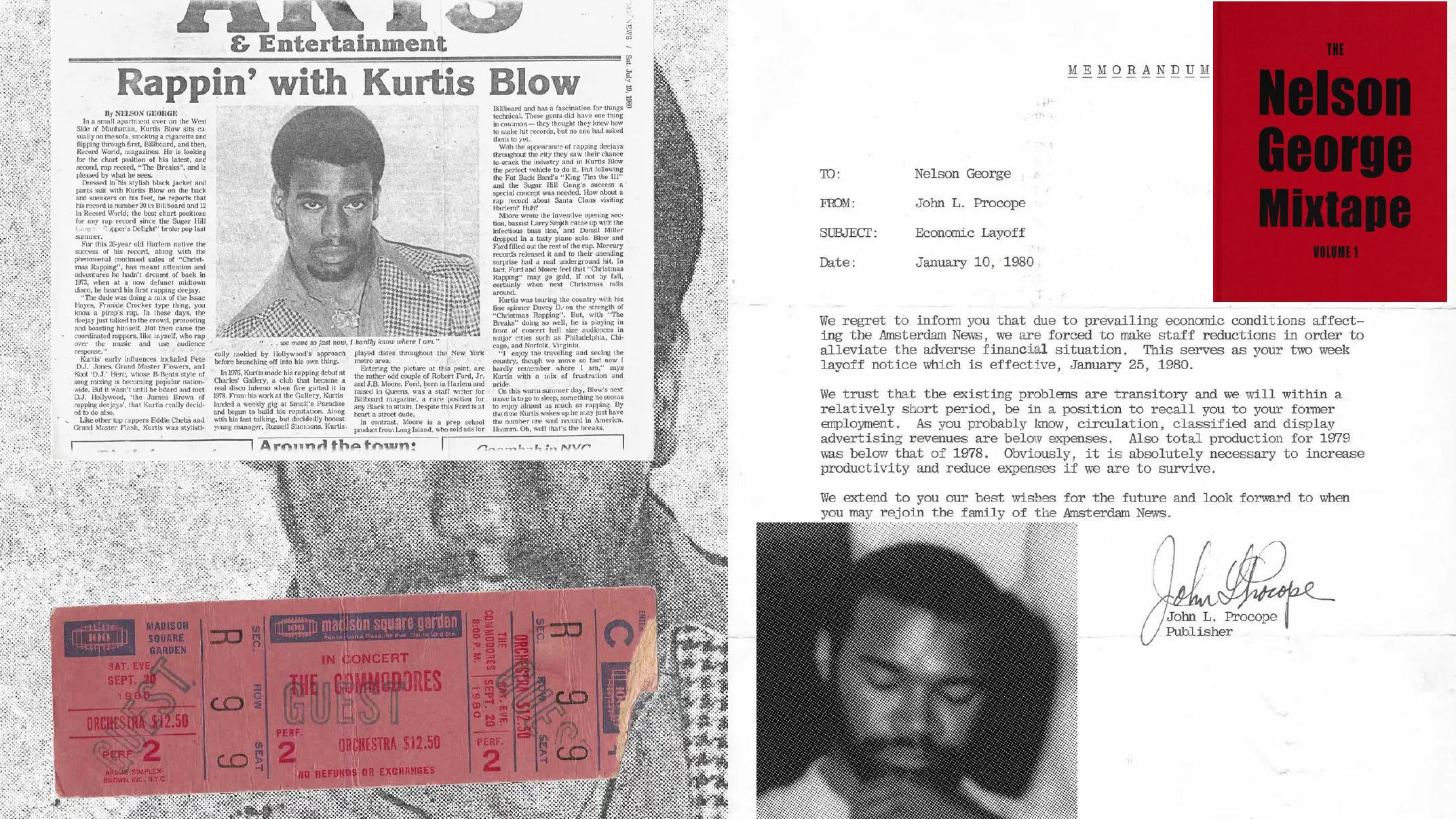

What really threw Vinylmania into the limelight was there's a guy named Nelson George, a writer for The Village Voice, a lot of music publications. He wrote an article about the store. “There's a guy in Greenwich Village selling promotional items as collector's items.” Matthew, they were driving down from Massachusetts. They were coming from all over the place because no one had ever heard of this before.

It seems so crazy, because if you're a fan, why wouldn't you want these promotional items? Yet they were probably just languishing before people like you monetized them.

I made up my own prices on things that I rarely found. Like an example would have been Linda Clifford's "Runaway Love." I asked $50 for that, and I started hanging them up in the store. People loved it. People were like, "Where are you getting this stuff?" That's when the store really, really took off.

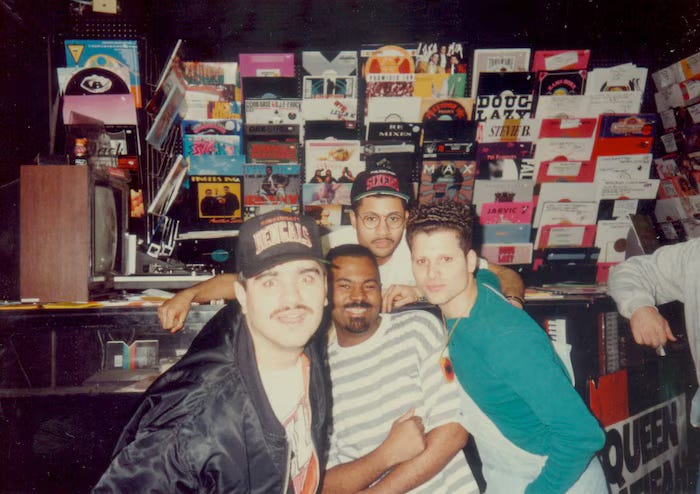

Can you describe what the store looked like, for anyone who never went?

It was very, very small, I'd say 15' x 50'. What I did was try to be a little innovative. There was this hardware store on 23rd St. that sold different kinds of racks. If you wanted to sell magazines, you got a rack for that. They all went onto pegboard with holes. You would push it in, and the rack would stand there and you could put items in it. I said, “What I'm going to do is I'm going to stagger my records. I'll be able to fit more if I bend them a little bit and I'll really fill the store.” When you walked in, the walls were covered with records — from the racks of records that you flipped through all the way up to the ceiling. I had a tremendous display on both walls. Of course, there were also the rows that you could go through and shop that way.

I also put up these wires, and I bought these little metal hooks and hooked the record, then hung it on the wire. All the collector's items were up on wires! That attracted so many people to come and see that. No other store did that before me.

And yet every store did it afterward — you're describing every record store I've ever been in.

I felt records were very visual to begin with, with the artwork. I figured, “Let me do it in a way where, when people walk in, they're going to be like, ‘Wow.’” People were wowed. That store was mobbed. You would walk by that tiny, little store and if you looked in, you would think there was something wrong in there, there were so many people crammed in there.

Did you have a lot of regulars?

I had a lot of regulars, but you got to remember, I'm talking about two different times with things because when the store did take off, it took off for a reason. In other words, I opened it up as a rock store. There was a rock store on every block in Greenwich Village. I had this little cardboard box on the floor where — I used to go and buy records from music critics or a person in the music business or a DJ, and I'd get different things. I didn't put a lot of value into what is known as a 12-inch single, because back in 1978, not a lot of people even knew what they were. There were people who knew what they were, but I used to put them in a box for $1.99. I put them down there and I started noticing a lot of people were coming just for that box.

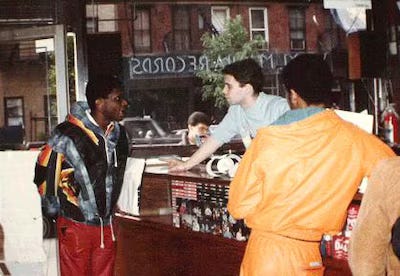

Two guys that lived on Christopher Street, Cliff and Steve, a gay couple, great guys, they came in the store all the time, and they were always in that box. I said, “What's up with this stuff?” They said, “You should go see a store on 42nd St. and Sixth Ave. It's in the subway station. He sells this stuff, and he sells a lot of dance music.” I didn't know anything about it. I went up, me and my wife, Debbie, took the train. Matthew, we got to the store, you couldn't even get in the place. The place was mobbed. I said, “What the hell is this?” I went in and they were selling 12-inch singles and 45s, and they catered to DJs. I said, “Wow, that's very interesting. I mean, maybe we should get into this.”

Cliff and Steve, they said to me, “You know, Charlie, you're in a perfect place to really make inroads into the gay community down here.” I said, “What do you mean?” They said, “Well, most of the guys” — at that time, the gay community was focused on Christopher Street, the Village. This was the '70s, the early '80s — “You can get all the guys that are living down here. They don't even like getting on the subway to go to that store. If you start selling not only these promo things you got, but there's a lot of imported 12-inch stuff...”

I didn't even know what that was. I found out where to buy imported stuff, especially from Canada up on 10th Ave. & 50th St. — Sunshine Distributors. I went to them, and I said, “I'm going to open up a store in the Village. I'm going to sell dance music.” They said, “You'll never be able to compete with Rock and Soul,” which was on Seventh Ave. & 35th St. — “or with Downstairs," the store in the subway. I decided to give it a run.

The gay community stopped going to those stores, and they started coming to mine. We were mobbed!

I took the store next door. It was separated by a hallway, and I made the right side a dance music store, and the left side remained the rock store, separating the genres of music. But the gay community took to us like you wouldn't believe. I mean, forget about it. They loved us, especially my wife.

My wife Debbie used to play the records. We only had one turntable. Someone would come in and say, “Can I hear this?” She'd put it on for them. She did that all day. And business went through the roof. I mean, I'll never forget when I used to go to my parents’ for dinner every Sunday, and I was working for the Board of Ed at that time, so I only did it part-time. I had people working there for me when I went to do my teaching jobs, and I told my parents, “I think I'm going to leave the Board of Education.” They were shocked! “What are you talking about?! Are you out of your mind?! You're giving up your pension! You're giving up your medical stuff!” But I really thought we we're going to make a run for the money with that store. They were flabbergasted by it. And literally, the store — between 1980 and 1985 — we were on a roll like you wouldn't believe.

It sounds like it was almost a community, like a culture, to go into Vinylmania.

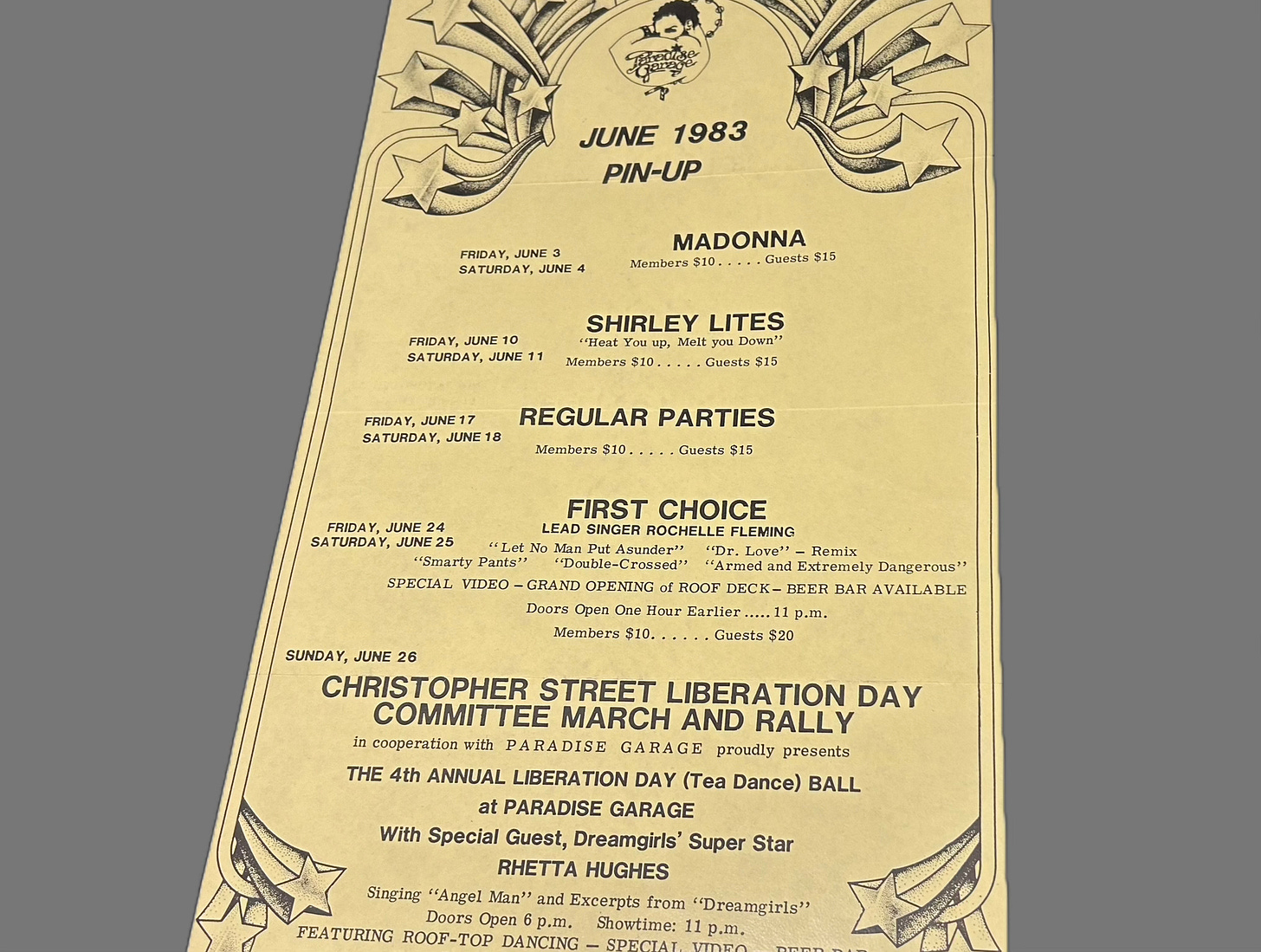

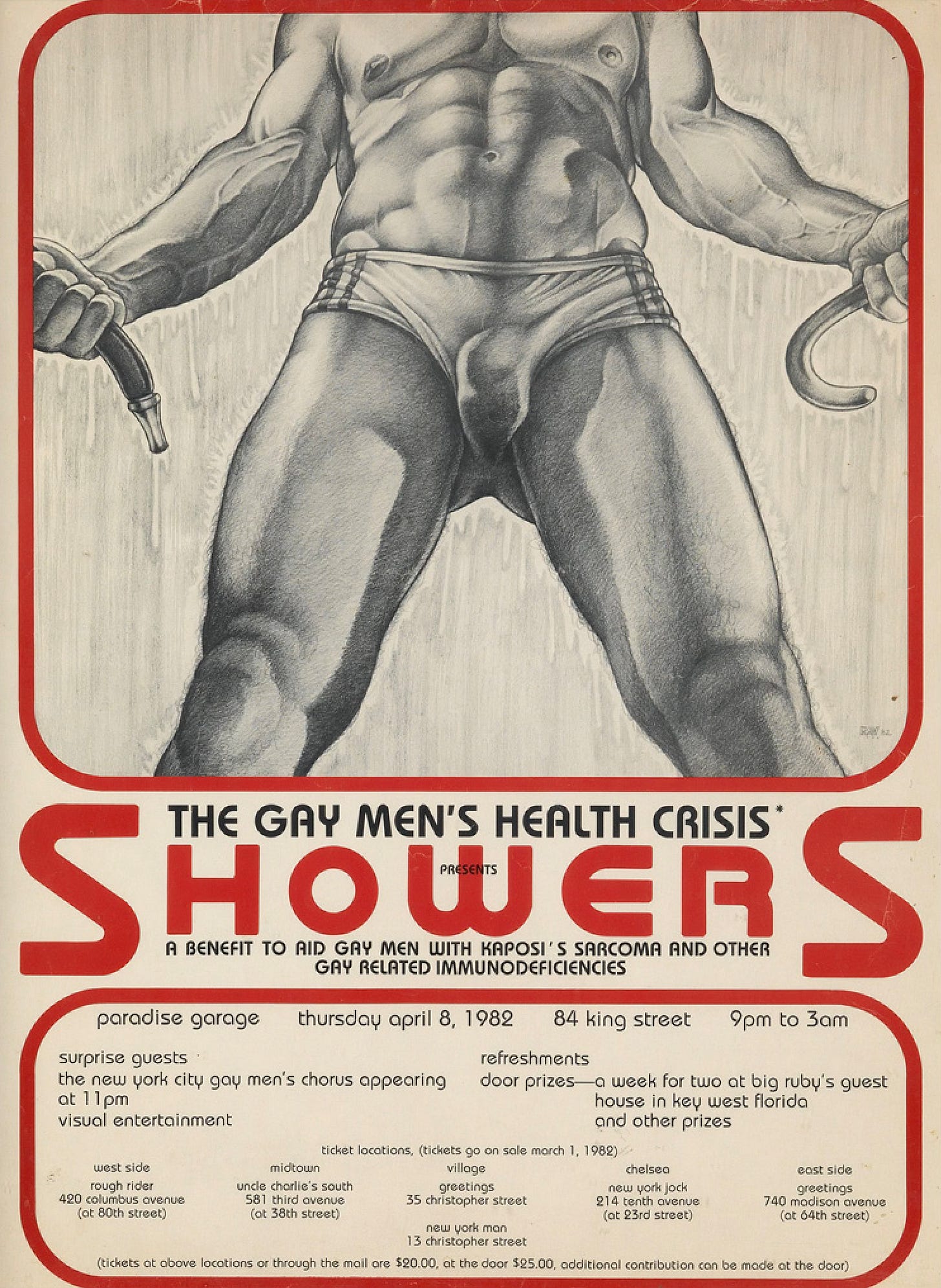

Absolutely. It's the perfect example of being in the right place at the right time, not only because of the gay community down there, but also the Paradise Garage was literally around the corner. I didn't know anything about the dance music scene. I didn't know a thing. So not only was I around the corner from this club that was extremely influential on what we sold, we were in Greenwich Village, which at that time, like I said, the gay community, Christopher Street, that was the focal point of things. We had a great time doing that and met a lot of really great people who became daily customers — a lot of guys lived in the Village and would come every single day to my store to see what was going to be put in that box, including working DJs.

Did you ever go into Paradise Garage?

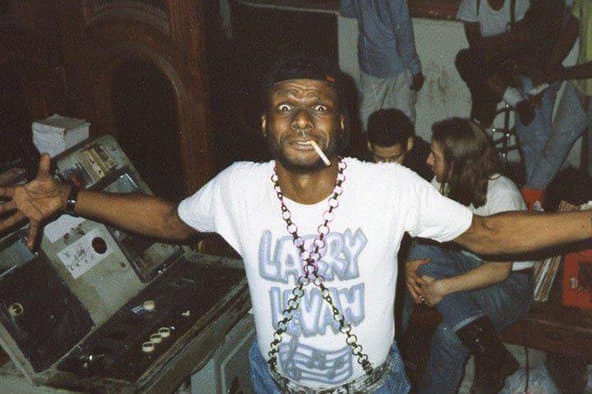

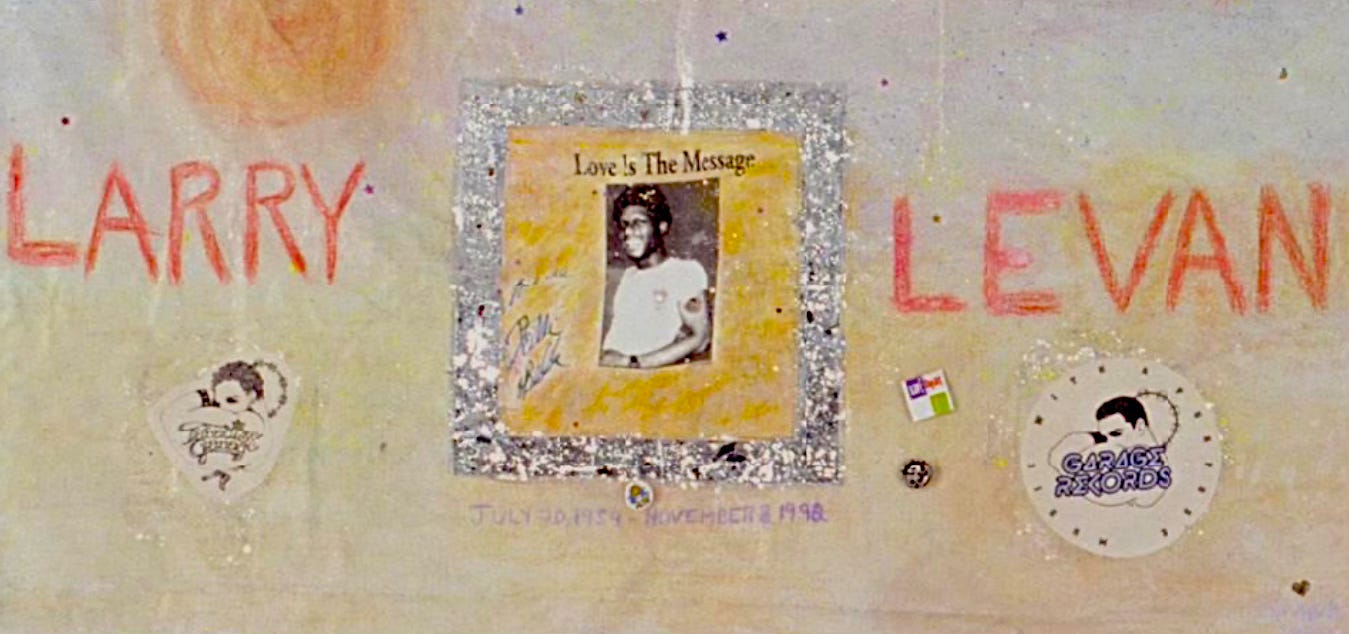

Many times. How that spilled over to me was we would get down to the store on a Saturday morning, we'd open up at 10, 11 o'clock, whatever it was. When we would get there — it started happening gradually — when we'd get there, there'd be people waiting outside, maybe four or five guys waiting outside. “Are you opening up the store?” “Yeah.” “Do you have any records that Larry played? Larry Levan.” “I don't know what that is.” “We're coming from the club around the corner. It just closed. We were wondering if you sell any records like he plays.”

Madonna’s “Everybody” video — her 1st — was shot in the Paradise Garage:

I didn't really sell them at that time. Remember, I had the little box with the promos. But then, a few years later, you'd come to my store, there could be 25 people waiting outside. This is when I started selling the 12-inches — regular ones, promo ones, imported ones. Forget about it. We would get to the store, within one hour, we would do $1,000, which was incredible at that time.

I learned all about Larry Levan. What he was playing, we'd have the next day. I hired two people that used to go every weekend. They would say, “He played this last night, he played that.”

Then, I got to meet him, and then it started working the other way. In other words, I'd have a record from Germany that Larry didn't have. I'd say, “I think you'll like this. You could have it for free.” He'd play it. I'd sell 150 copies the next day! It was unbelievable. Now, all of these stores that were in the Village weren't really doing this. They were selling rock. When my store started doing business like this, they had never heard of it. “What do you mean you sold 150 copies of it?!” Because with rock albums, I guess you could do that, but with these 12-inch singles, it was mind blowing how they used to sell. The club was a big influence on it.

Sounds like true, organic word of mouth.

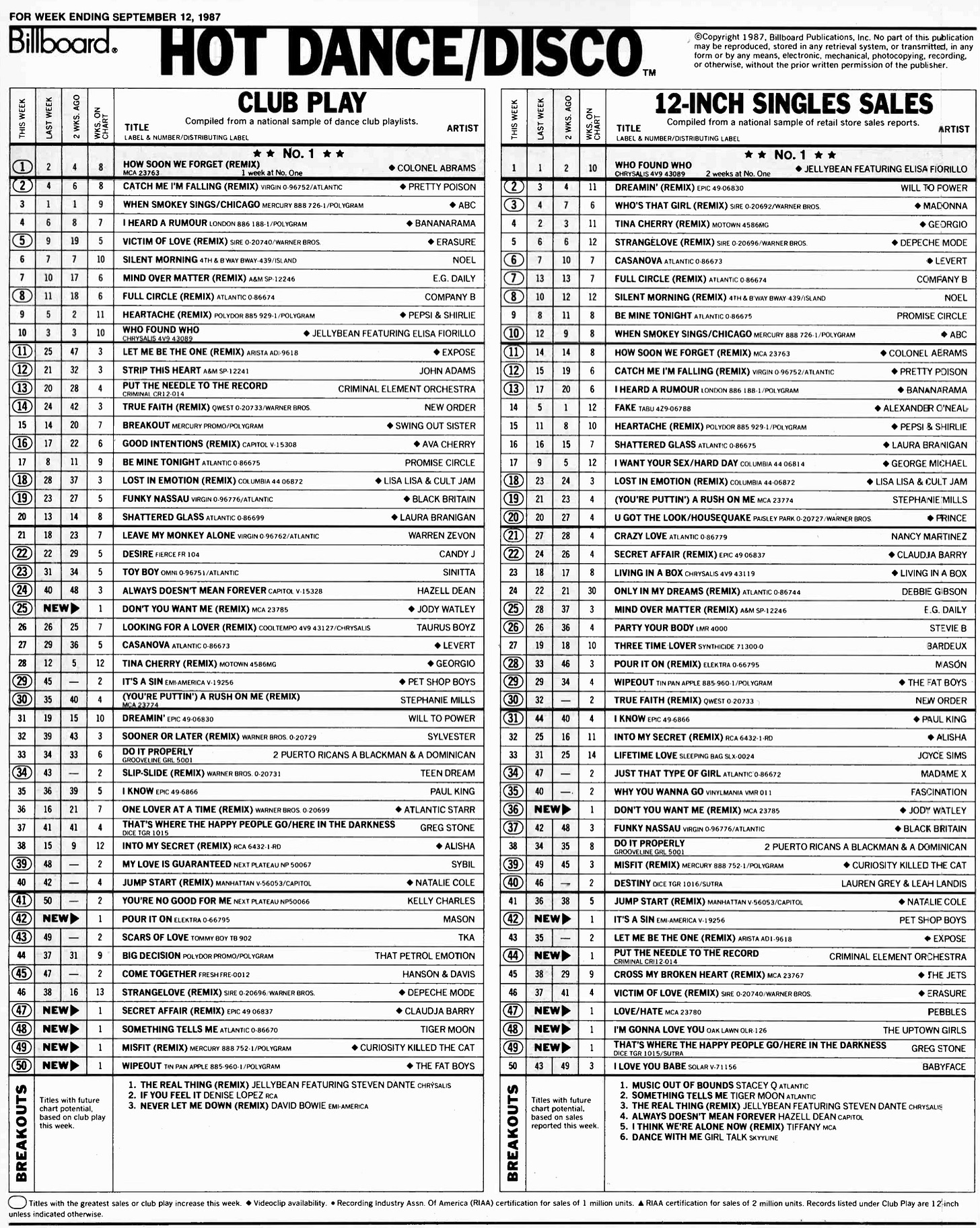

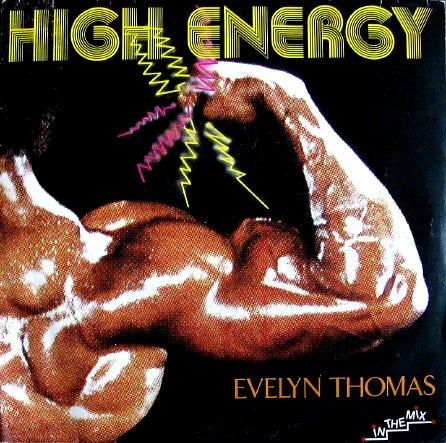

It was amazing. I had two crowds coming. I had the Paradise Garage crowd, which on a Saturday night, it was more gay at the Garage than a Friday night. They were open Fridays and Saturdays. But I had the Paradise Garage crowd coming, predominantly Black. A lot of white people, too, but predominantly Black at the Garage. Then I had the gay community coming. The Garage people, some gay, wanted disco, R&B, soul, and the gay clientele wanted HiNRG. We did things where I had a guy playing records at the counter. I wasn't one of these places where you come in and play it yourself. I never really believed in that. I felt that if a guy's playing the right records, he'd put on a record, 10 guys might say, “I'll take it.” You make 10 sales, put on another record, it doesn't go over that well, you only sell a few. Put on another record. People will also ask, “Could you play this? “You sell 10 copies of that.

The Paradise Garage crowd wasn't into HiNRG. It was a different style. It was still soulful in style, but ... anyway, I loved it. It's not like we got complaints, but the people that were waiting to hear more Garage stuff were like, “Come on, we're going to listen to this HiNRG all day?” The HiNRG people were like, “Hey, we don't really want to hear what you want to hear.” A guy actually saw that, and he opened up a store on Christopher Street called Decadance. A lot of my gay clientele in 1985, 1986 started wandering over there out of interest.

That's when house music started out of Chicago. I decided to head in that direction. Since we had new competition with the HiNRG, we went toward house. We did it for the next 20 years.

Can you backtrack a little and describe what it was like going to Paradise Garage?

Extreme! Something I had never seen before in my life. Loud, blasting music, incredible sound system. First, I got to say, because I had the record store, I was treated like royalty there. As soon as I would get to the door — there'd be a line — they said, “The guy from the record store! Come on in.” I'd also get to go right into the DJ booth. You had to go up a ladder, like, a set of stairs, to get up to Larry's thing. I was treated a little differently than a regular customer. But the experience was unbelievable, but also something I, at 30 years old, had never experienced.

What I'm saying is, to go to the Paradise Garage, you had to get there at 4 in the morning. I was a regular guy, going to bed at 11, 12. “Oh, no, Grace Jones is going to go on at 4!” And she'd really go on at 6 in the morning! Seriously. In other words, people would be in there from midnight till noon the next day.

The number of times I went to the Paradise Garage, I threw my whole weekend off. I ended up sleeping all day Sunday.

You had to see it to believe it. It had a magic to it that I don't think was ever duplicated in any other club.

Read about the end of Paradise Garage HERE

What was Larry Levan like?

A little eccentric. I mean, I tried working with him when we started a record label. He worked at his own pace. He was a very nice guy. I got along with him. I had this couple, Manny Lehman and Judy Russell, that were best friends with him, so I would get all the inside info about the music that we needed to know about. Then he became a customer at the store. He would come in all the time and I would give him recommendations on what he should play at the club. He was extremely influential, in regards to radio. If Larry played it, Frankie Crocker was going to play it on WBLS. The club was groundbreaking.

He broke records that you wouldn't even believe. But an example would be “I Can't Wait” by Nu Shooz. That was a small group living in, I think, Portland, Oregon. They called the store. They said, “We hear Larry Levan is playing our record … ?” I said, “Yeah, he bought it here at my store.” That record was signed to Atlantic because he played that thing.

I remember dancing around to it in my room as a kid.

“I Can't Wait,” you see, that's what made Larry different. I mean, you know the song. It's not really a dance record. I mean, it's like, “Can you dance to this?” But Larry played that record. Forget about it. Never forget, Larry Yasgar from Atlantic called me. It's when I met him. He said, “I heard you have a record down there called ‘I Can't Wait.’ I need two copies." It was out on Atlantic a couple of weeks later. He signed it. He put it out. They did great with it. Larry Levan, he did that. Whoever doesn't give credit for that song to Larry Levan doesn't know what they're talking about.

Can you talk a little about the Vinylmania record label you ran for a while?

The song I wanted to put out, that I wanted to license from an English label called Record Shack, was “I'm Living My Own Life” by Earlene Bentley. It had a meaning to it. I mean, it was a gay statement. I thought it was perfect for us. But I flew over to England to do a deal with them, and the record was already taken. By the time I got there, it came out on a guy named Tony Valor's label [TVI Records & Filmworks]. Manny and Judy suggested doing something with Larry. I did my first two records with Larry. It's not that he was hard to work with — we should have done a lot better with the records that we put out with him, but we just didn't work well together.

I discovered the label business wasn't for me. I was too used to people coming in, giving me the money for records, leaving the store very happy. The label business was, I don't know, like, a bunch of liars. I mean, first of all, you didn't get paid for 60 to 90 days. Then, it would be, “We have a return. We didn't sell this.” It was just a lot of, “The check is in the mail,” and they're stabbing you in the back at the same time. It wasn't for me. We did about 18, 20 records, and I said, “I'm not doing this anymore. I'm making plenty of money selling the fucking records. Why do I got to put them out?”

Before we move on, along with Larry, did you meet the other famous DJs of the era?

I think that most DJs came into the store at least once. Not every DJ liked Vinylmania, but I met all of them, from Robbie Leslie to Michael Fierman. I always felt if you didn't come in to Vinylmania as a DJ in New York, I mean, where the hell were you?

When did you come up with the idea of doing in-store events?

Right from the beginning, we started getting requests for that. We had a lot of people come to the store. We had George Kranz. He did “Din Daa Daa.” It was a weird record. But he was from Germany, and he came to the store. Nobody came to that in-store. Nobody came. But then we had in-stores where you couldn't get in the door.

One of the biggest ones we ever did was with Raquel Welch!

People at that time in the music business had heard that we did in-stores. Columbia, at that time, they were doing a Raquel Welch 12-inch. She didn't do an album. She just did a 12-inch. She was in New York and she says, "All right, I want to go to a record store and see how the record does." They said, "Then you have to go to Vinylmania." It was this tiny, little store, really. She came and it was amazing. It was on the cover of The New York Daily News. It was amazing!

It seems like she wouldn't be a good match for your store because she was someone who was dabbling in HiNRG.

I think that the day she was there, there was probably people who came to that store that day never came back. [Laughs] She was a movie star, and she was gorgeous. The line went down the block, and people brought magazines with pictures of her and a little something they wanted her to sign. “Can you sign my T-shirt?” She got there and she couldn't have been sweeter. My father was there that day — I'll never forget that. She said, “Charlie, I'm here to sell records. If anybody wants my autograph, they have to buy one.” I said, “Great. I like you.” We sold I'd say 200-300 records that day of her records. It was an incredible experience with her. One of my favorite ones. I got a lot of pictures of it. It was on the news at night.

Who else did you have?

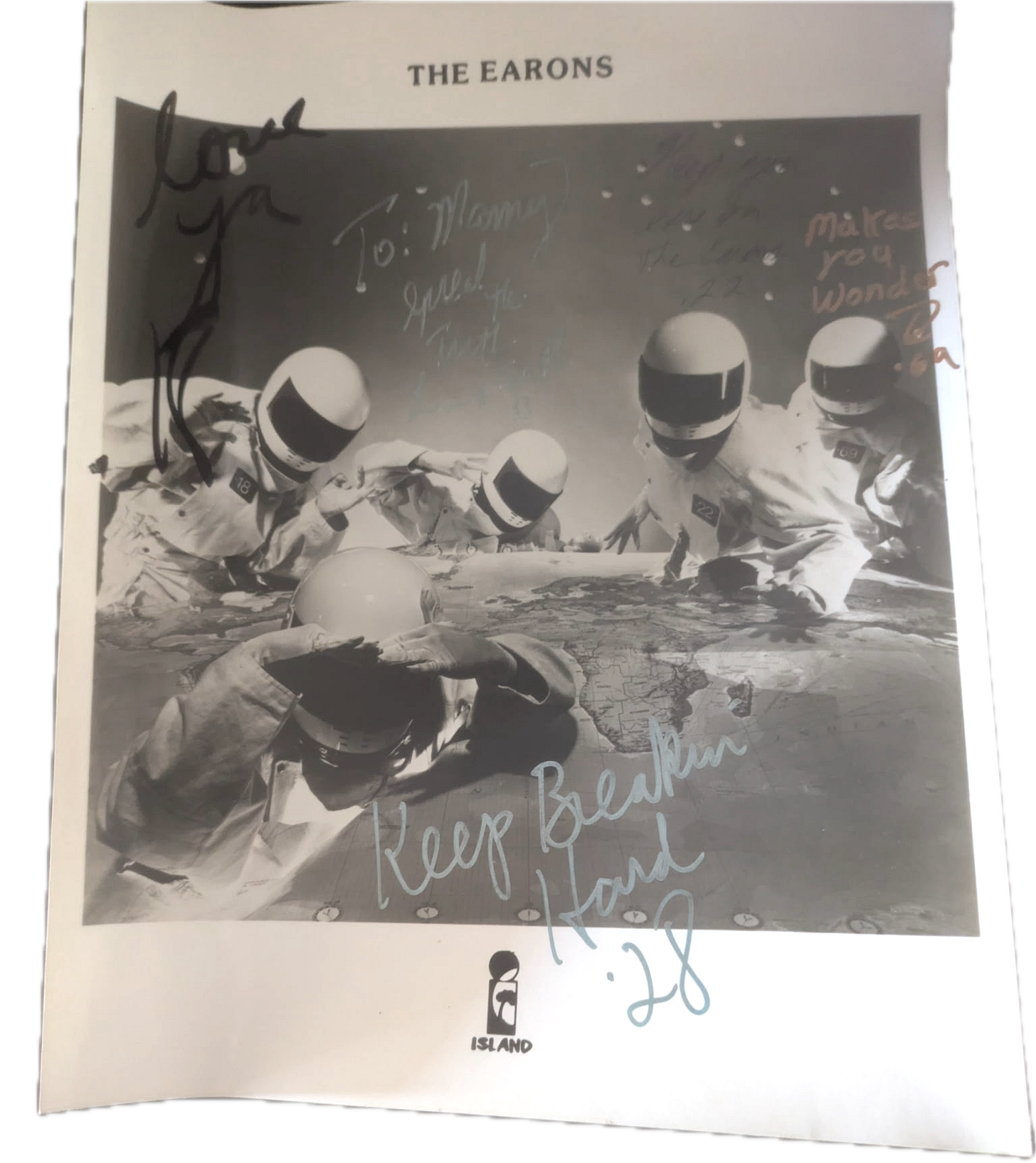

Yeah. We did a weird one with a group called the Earons. They were on Island, and they used to dress in these Hazmat suits. You didn't really see them. There were four guys dressed in Hazmat suits, but you didn't really know who was in the suit. We did one once with the Latin Rascals because they had a song out called “Arabian Knights,” and they came to the store on a camel. The camel was crapping on the street. The people on Carmine St., they called the police. The police came, “Do you have a license for this camel?”

All of the house music artists came to the store — all of them. We used to get a lot of people from overseas, too. We started getting known over there. We did big British business. Then back in the early '80s, we started doing a little mail order because, let's say there was a DJ in Colorado and he wanted a certain import, we would send it to him. It was like another little offshoot business. We started with the mail order, which was nothing anybody did back then.

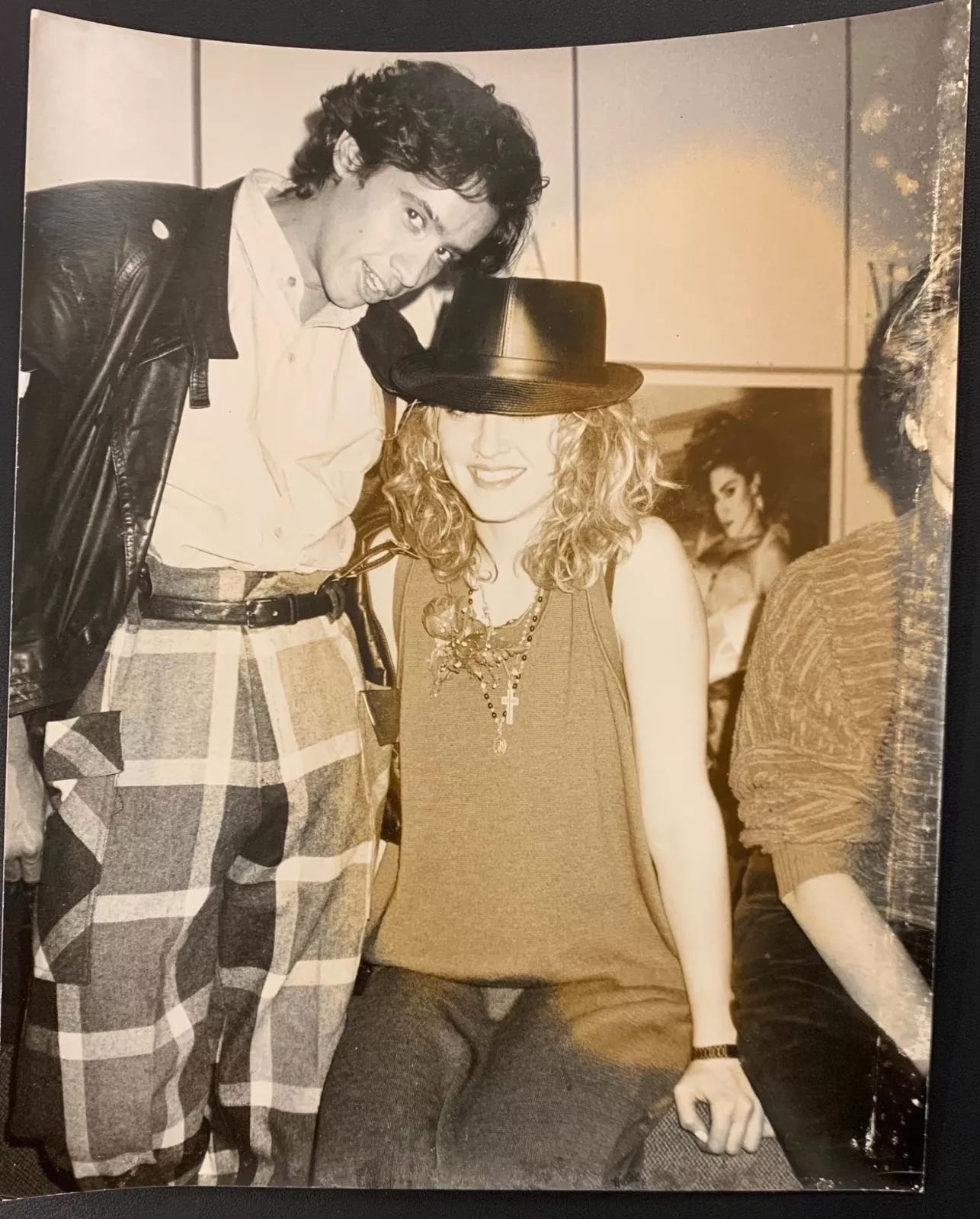

Now we have to go into the Madonna signing in 1983. Her first of only three she has done in 42 years.

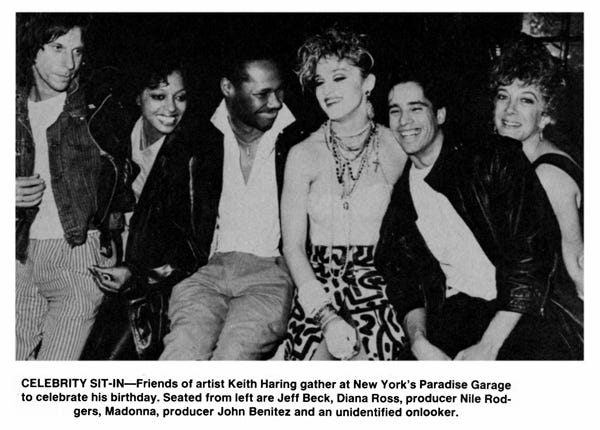

What happened was I had a guy that came regularly named John Benitez.

Jellybean!

Jellybean. At that time, Jellybean was doing a lot of remixes. He was a big DJ. He had his own club called the Fun House. Now, the Fun House, which was on 26th St., had a lot of influence on Vinylmania also, but they came from a different point of view than Paradise Garage. They played a lot of what was known as freestyle, and it was Latino-based. I also sold a lot of freestyle besides the HiNRG, besides the house, besides the imports, besides the promos. I was getting into it in a very deep way and learning all of this new music. Fortunately, the one thing I got to say, Matthew, is I liked the music. If I didn't like it, I think it would have been an all-different world. I can't imagine selling something you don't like. People hated disco. After getting into it, I said, “What the fuck are they missing here? This is incredible stuff.”

So, Madonna came from Jellybean. He said, “My girlfriend, Madonna, is putting out a record." I think it was “Everybody.” I had heard of Madonna through Danceteria because there was this DJ there named Mark Kamins, and she went to the club with a cassette. Mark Kamins, I think, had one night of sexual relations with her. [She playfully discusses trading sex for what she wanted HERE. — Ed.] Then he brought the tape over to Seymour Stein at Sire and he signed her. I had heard about this. I had wanted to meet her, so Jellybean started bringing her to the store. She would come when he would shop. When the record came out, I said, “Why don't we do something?” And she said, “Great.”

If you would have told me she would become what we know now, I would have never ... I just thought this was a one-hit wonder.

Most 12-inch artists did a couple of those and you never heard from them again. If they did an album, you were lucky. But she was talented. She was writing her own stuff. Who the hell was doing that? She was very, very unique. When the first album came out, she wrote most of it with her boyfriend mixing it. I mean, it was a phenomenon that not many people had seen before.

She was going out with John, and then I think they broke up, and then I never saw her again. I'd occasionally see John.

The day of her in-store — August 26, 1983, at 7 p.m. — first of all, how did you promote it? How many people came?

I put out one ad for one week — and that was all we did. And through word of mouth, if we got 50 people in [the 52 Carmine St. location] in the couple of hours she was there — I don't even think we got that. I really don't. It was very minimally attended. But remember, no one knew who Madonna was. It just wasn't a big deal. [Even less rosy memory of the event HERE. — Ed.]

I found her to be a very weird person. I mean, it's not that she was cold. She just didn't talk that much. I'll never forget, she said to me, she came to the store with Jellybean and she said, “I heard you bought a loft,” because we bought an apartment. I was the super of the building. I told the guy, just like I told my parents, I told, “Hey, look, I can't really do this job anymore. This record store is going crazy,” or whatever. “I'd like to rent an apartment for you,” I told them. These guys had like 700 apartments around New York. He said, “How'd you like to buy an apartment?” I said, “I don't know what you mean.” He says, “I have apartments. They're going to be condos, which in the '80s, I never really knew what it was. He helped me buy this apartment for $155,000 on W. 17th St., and she heard about it. She said, “I never saw one. Can I come over?” So, we were closing the store, and I called my wife, I said, “I'm coming over with John and Madonna.”

[My wife] was pregnant at that time. She said, “Why?” She came in with her Madonna look and a bag of jawbreakers, a little brown paper bag of 'em. She had a whole bag. She came in, said hello to my wife, came in, looked around a little bit. They stayed for a half an hour, and they left. That's the last time I saw her in person.

You not only hosted her first signing, you were a person who impressed her and got her attention!

It was a pretty impressive loft, too, 20-foot ceilings. It was a unique little space. I wish I still had it.

Can you talk a little bit about the people who worked for you in the store — what were they like?

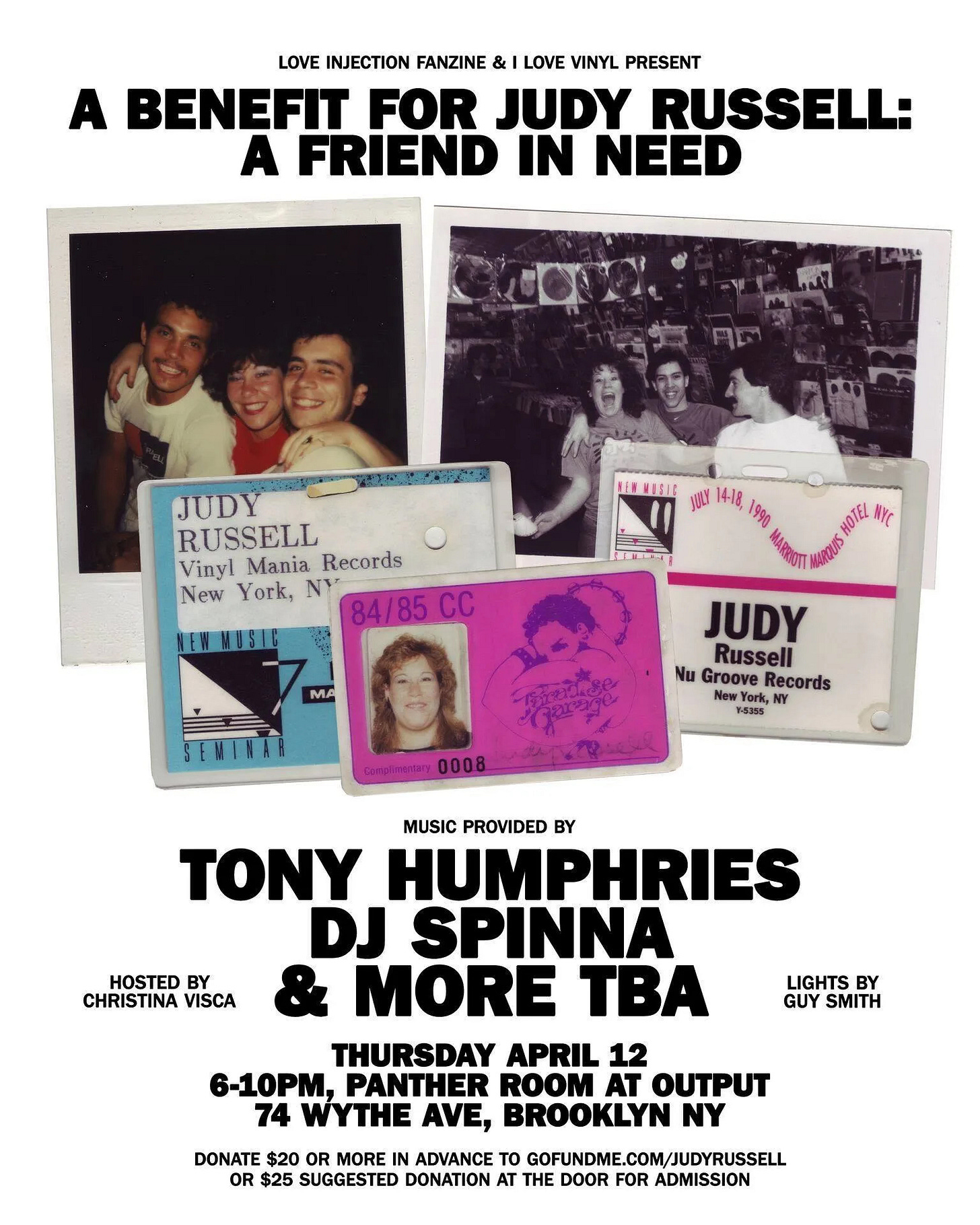

Well, besides my wife — who I couldn't have done it without — Manny and Judy stand out as the two people who really brought a lot of attention to that store. They both went on to be successful in the music business after they left the store. He went to California and worked for A&M, became a well-known DJ out there.

Judy, unfortunately, passed away, but she worked for a lot of distributors, independent labels.

Another person who stands out in my memory was my first-ever employee, José Bonilla, who taught me a lot about promos. He was my first employee, and he was in a record pool — I didn't know anything about them. He was a necessity.

But I had hundreds of people that worked for me over the 29 years. Until this day, Matthew, I'll hear from people, “Charlie, working with you was the best work I've ever had in my life.” Working for me was extremely easy. I didn't even ask you to do anything! All you had to do was know the music. If you knew the music, you could work there. I had record fanatics, so they all wanted to work in there. They were there every day to see what was happening. I had people who were extremely happy to do their job, and to get paid to do it. I had people that worked for me for 10 or 15 years, and you could only go so far in a record store.

Jerel Black, he worked with me over 10 years. I had a store on the Upper West Side on 74th and Amsterdam. His father worked for the airlines. He wanted his son to get a job. He came to the store and really tore into his son. “This is what you're going to do with your life?! You're going to work in a record store?!” I was standing right there. I thought the father was going to attack me. He said, “Dad, this is what I want to do.” He stayed with me from 18 years old into his 30s.

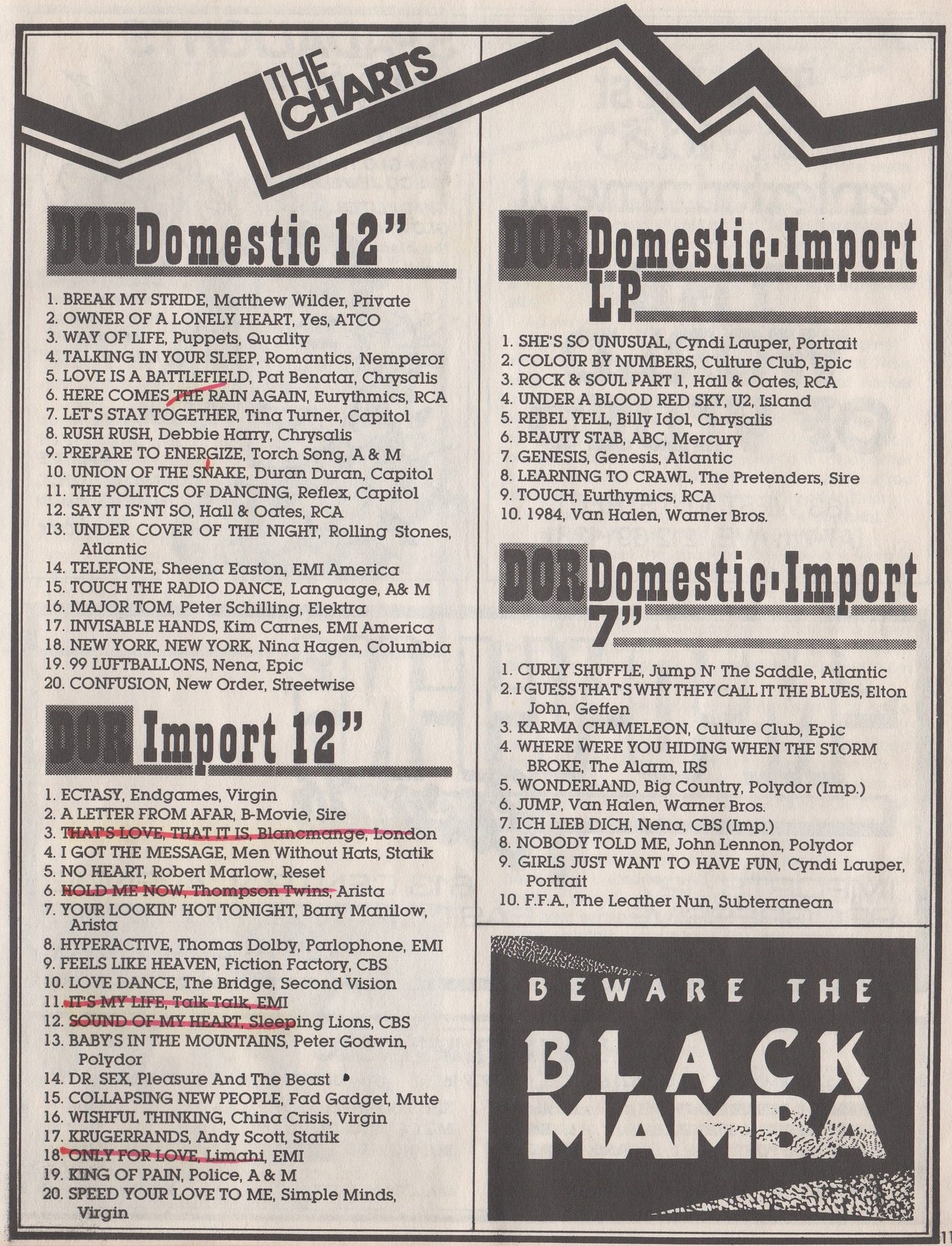

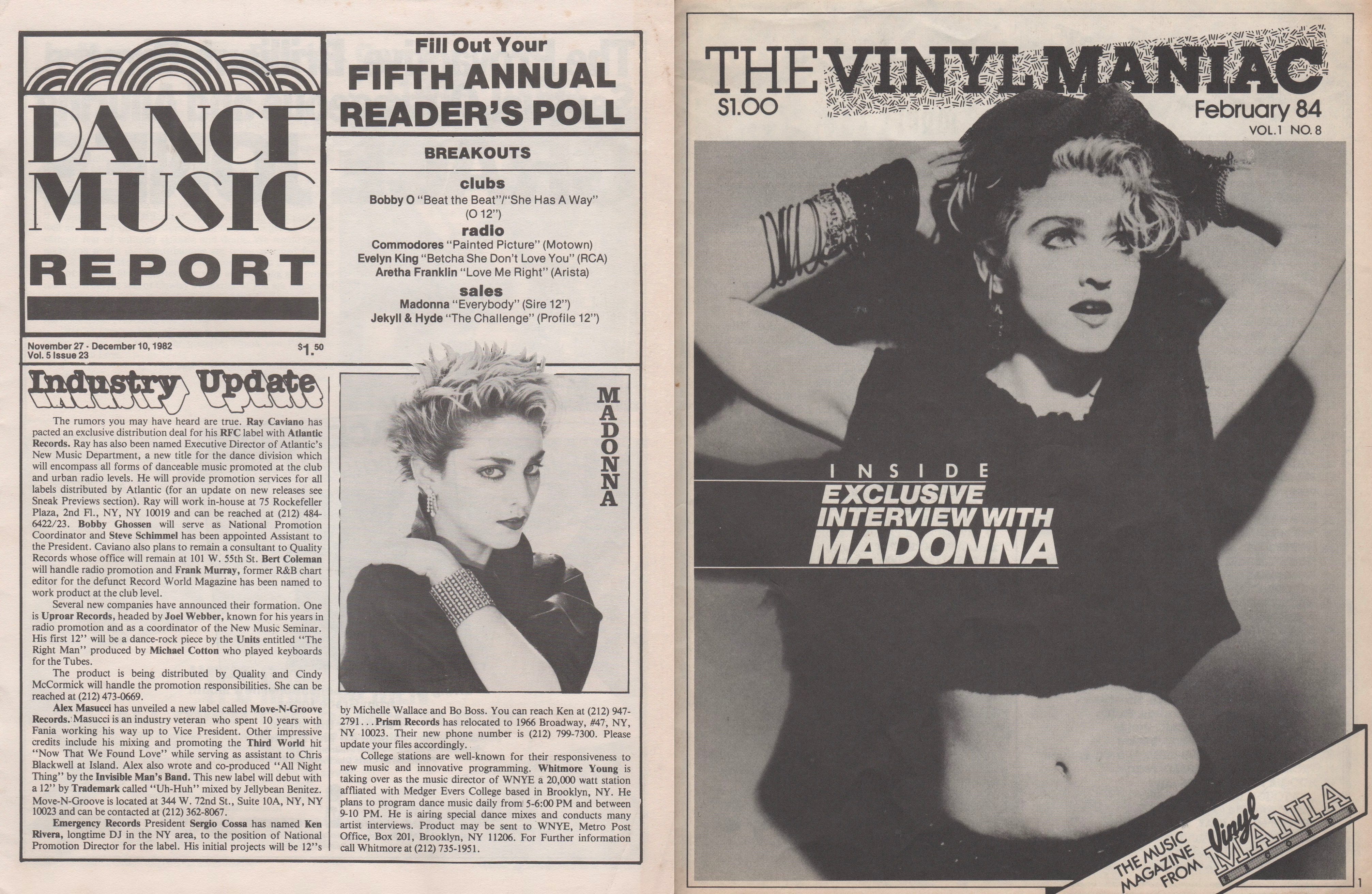

You also briefly published a zine called The Vinyl Maniac. How did you decide to start that?

Okay. There was a guy named Tom Silverman who had a record label called Tommy Boy. He lived on the Upper East Side, on 92nd & 1st. He started this magazine called Dance Music Report. This was in 1980, '81. I used to read it religiously. I got to know everybody who wrote for the magazine, and I got to know Tom. Manny and Judy, who were now part of my team, they said, "You know, maybe we could do something like this — even better." That's when we started. It was basically a Manny/Judy idea. I said, "All right, you guys get all your things together."

We found one of the customers that came in, Malcolm West, who as a graphic artist. He said, “I could do this for you.” It took off.

Unfortunately, we went through a very said time with the gay community ...

The AIDS crisis must have been something you saw firsthand, with your clientele and your location.

The first guy we heard about was a DJ named Joe Zeider, Z-E-I-D-E-R, died of something called AIDS. “What the hell is AIDS?” “I don't know. It's some disease.” Then it was “a disease that only gay people get.” It's a sexual disease? But it had an effect on my store that was devastating, because over the next couple of years, we started losing people like crazy.

You were at ground zero.

Exactly. We were right in in the center of it, and it was like ... You didn't actually know what it was. You were like, “What is this?” But guys started dropping like flies. Malcolm West was, unfortunately, one of these people that passed away. Malcolm was like, “I don't want any money for it. I'll just come in and take records when I need them.” After he died, we talked to a few people who wanted $2,000. I said, “You know, maybe this has seen its day,” and we just put it to rest after 18 issues or something like that. I don't even know how many.

Did you hand it out or sell it?

We were selling it in the beginning for a dollar, but with the first couple of issues, if you came in the store, we just gave it to you. I think we would have given Dance Music Reporta run for the money. What I mean by that is that they didn't really do interviews. Theirs was basically reporting what records were coming out, what's happening at the labels, a lot of reading. But we said, “Hey, let's interview Gino Soccio from Canada! Let's interview Jeffrey Osborne.”

Most artists would agree. I think we had a little magic there also that was attracting people to it. But after Malcolm died, that must have been about 1985, 1984, we just put it to rest.

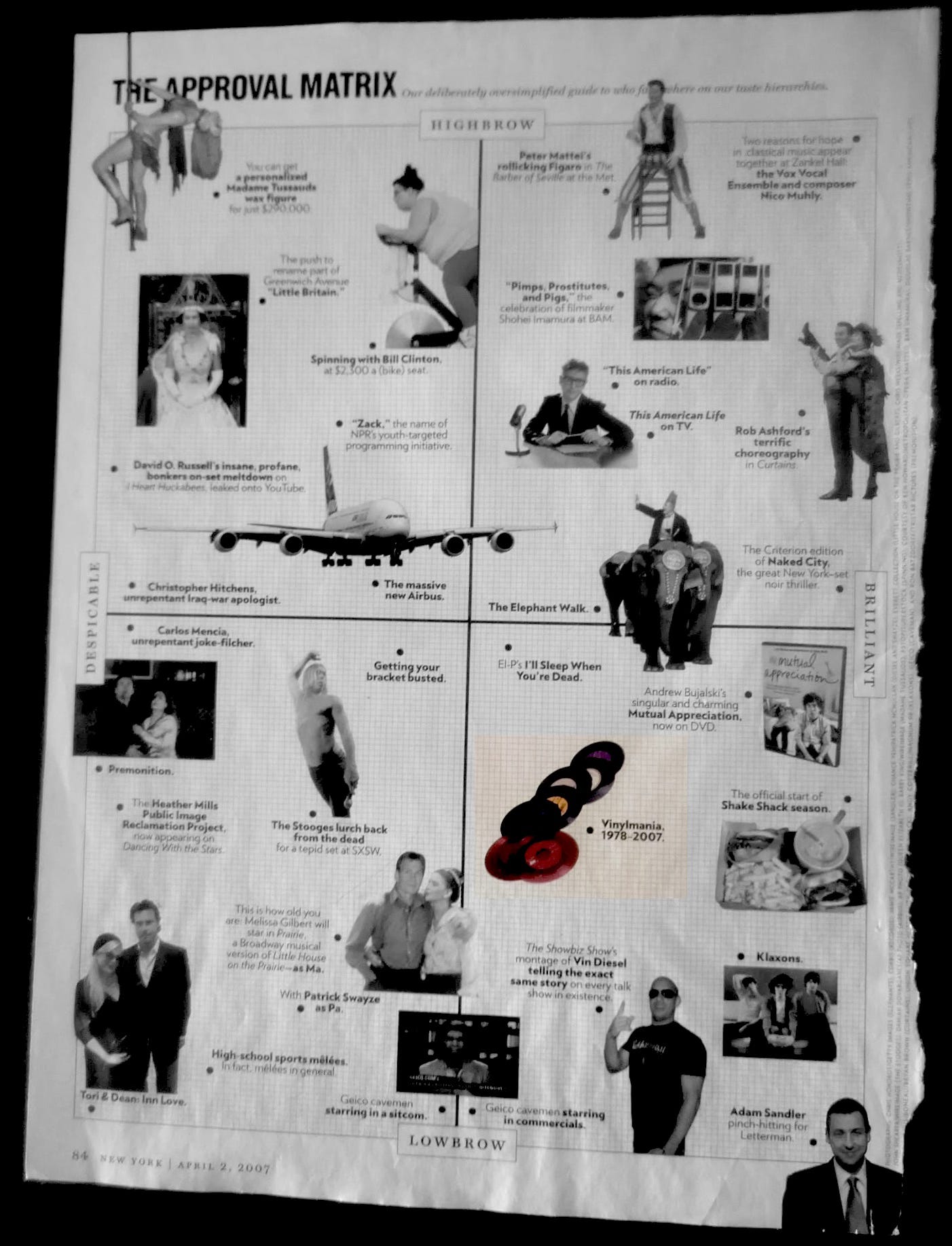

What made you walk away from Vinylmania eventually?

What made me walk away was the Internet started becoming competition. In 2007, I said, “Well, we're paying $4,200 a month rent here. It's $50,000 a year I won't have to spend if I do it from home.” So, at 57 years old, I decided to close it. I did it for 29 years. The guy who owned the building, Bob Cohen, came to me, who's a guy my age, maybe a little older. “Charlie, I can see that you love what you're doing. I'll let you keep the store at the $4,200.” When I left, he raised the rent from $4,200 to $10,000!

You had weathered all the changes in the music industry, but it was time?

Exactly. The big change was the CD. That was the big change. I said to everybody, I said, “Look, we're Vinylmania, and that's what we're sticking with. Don't worry about what you're hearing, that records are going to go away.” I just knew that that wasn't going to happen because I knew how much these guys love these fucking records. They were like, “This was their whole life. They're not going to switch. They're not.” And they didn't. DJs would come in and say, “Hey, Charlie, you're still selling records?” And I did it up until 2007.

And you know what? I could still be doing it today with the vinyl. ⚡️