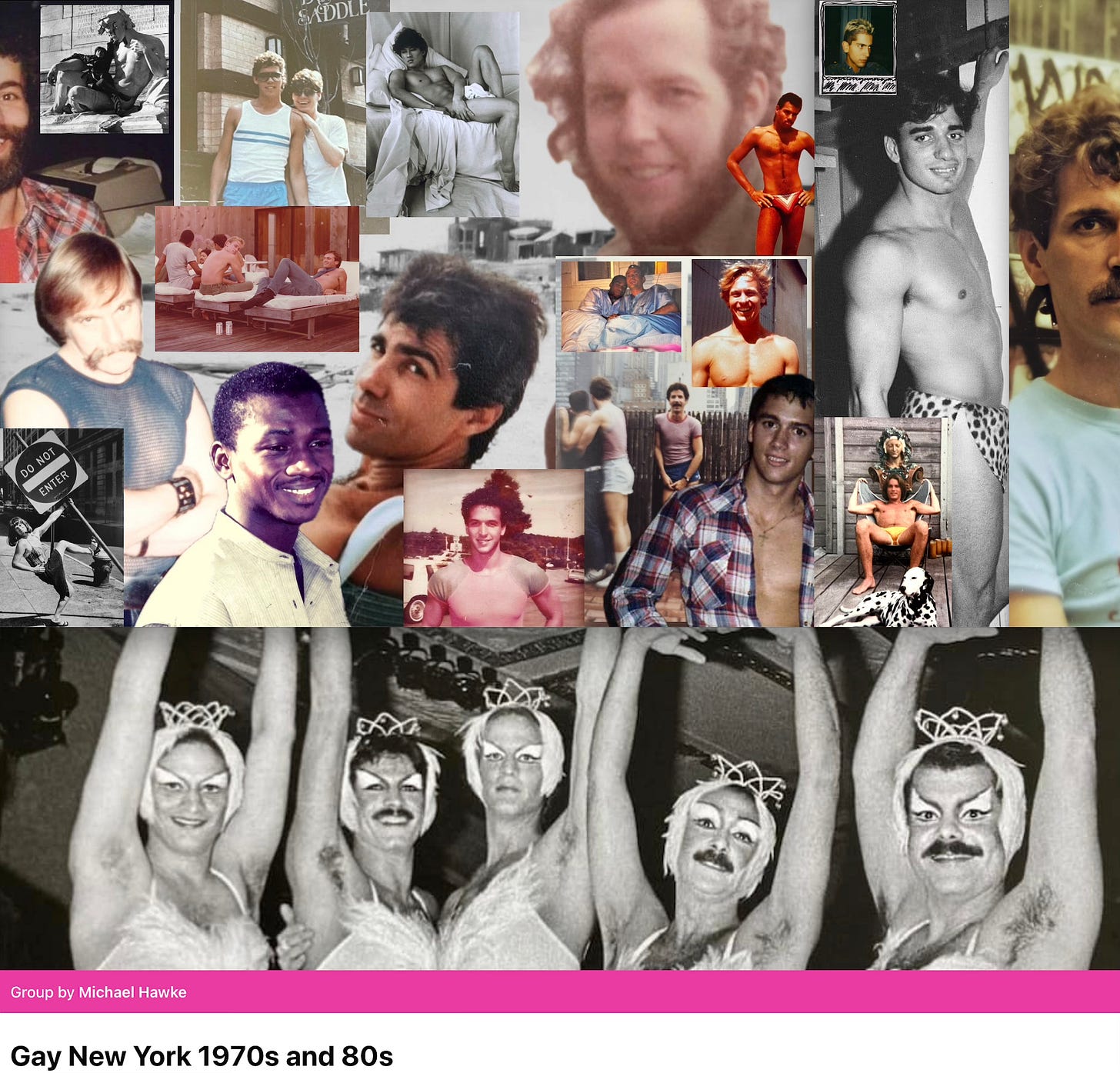

You Had to Be There: 'Gay New York 1970s and 80s' Founder Michael Hawke Morris Is Making History

How one man's desire to reconnect with his own past has brought a not-entirely-lost generation together again

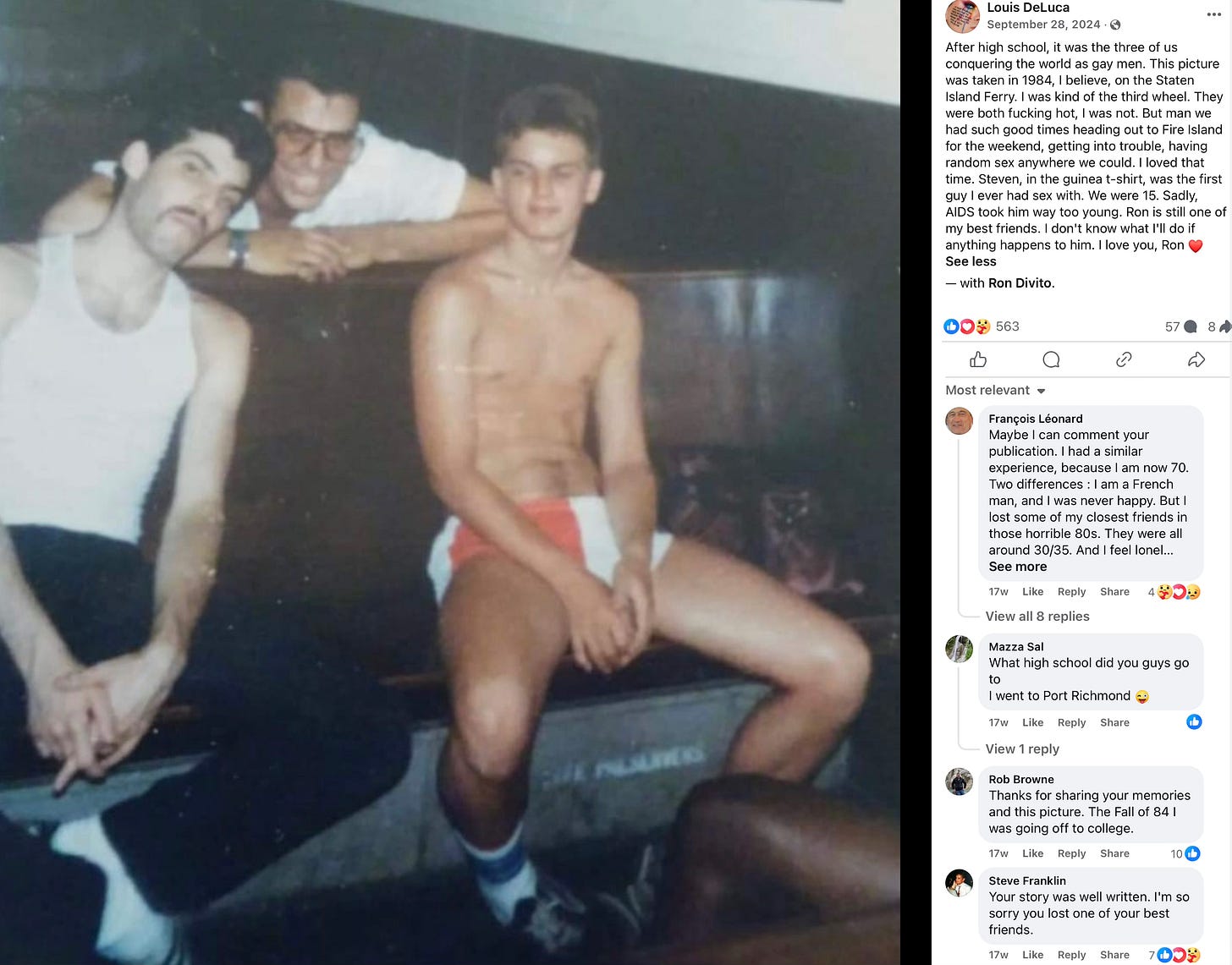

It was May 2024 when I noticed a gay Facebook group devoted to the New York City of 40 and 50 years ago, an era that encapsulated both a kind of nirvana for gay men in a post-sexual revolutionary society and a very real hell as AIDS took hold and refused to let go. It truly was the best of times and the worst of times, and that juxtaposition served to make the era singularly important to a community, searing it into the memories of those who first enjoyed — and then survived — it all.

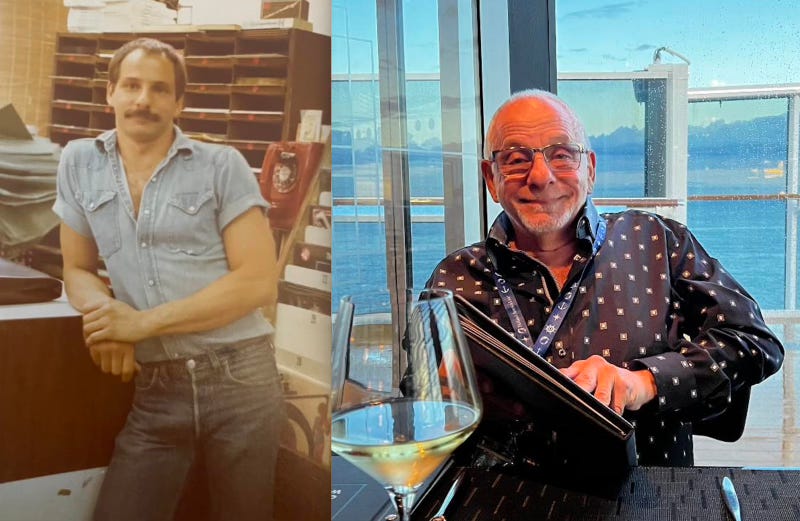

The first post to catch my eye was a '70s image of a handsome (okay, let’s go period-specific, humpy) clone packing heat in his jeans and smirking under his porn ‘stache alongside a current snap of the same man, now silvered and in his 70s — but still grinning.

The immediate impact was not to assess what had been lost in the past 45 years (to be fair, he started out looking like Al Parker so had a leg up on “aging well”), but to assess how fortunate he was to be here, enjoying a glass of wine, in a photo obviously taken by someone close to him.

Such is the unspoken effect of glancing through Gay New York in the 1970s and 80s, a group launched by former NYC transplant and working actor Michael Hawke Morris, 70 — it is a visual language of joy, and of relief.

“He made it,” we think, looking at the images. “We made it.”

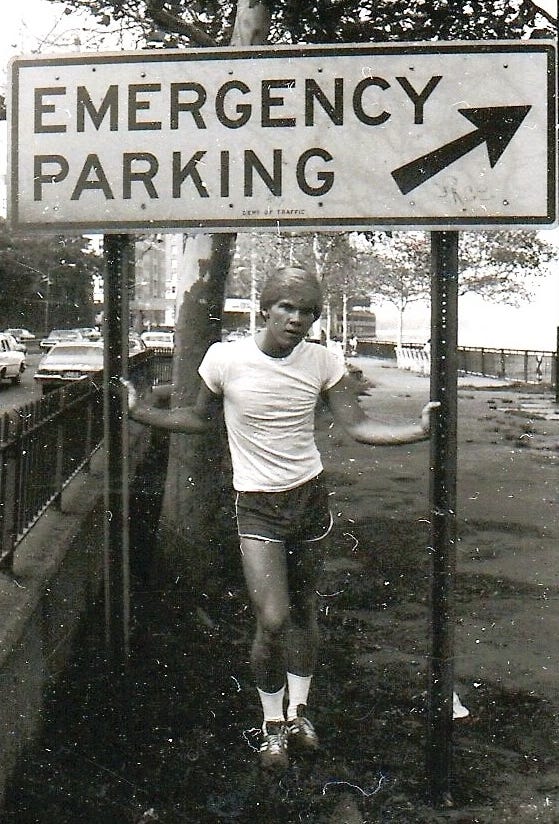

Even better, the group goes beyond the surface, encouraging members to contribute written remembrances of people and places past, leading to an engrossing mix of fleeting moments and deeply personal essays in what has blown up to become a vital oral history of what it meant to be LGBTQ+ in Manhattan in that fateful time.

Shortly after I found it, the group ballooned from 600 members to tens of thousands (44,000+ and counting at the time of this post), a shocker for Hawke Morris, who was initially spurred on by the isolation of COVID-19.

“Part of it was giving back, which is not my most natural inclination,” says Hawke Morris, who now lives in Virginia, of his early motivation. “My dogs had recently died. My brothers live close by, but I'm not really close to them. I felt very isolated. I started writing, pulling things out of my basement, and I couldn't stop. The first few days, I wrote 14,000 words. Then — I know it is ridiculous — but I eventually wrote 1.5 million words about my years in New York.”

Hawke Morris, who will soon celebrate 37 years of sobriety after being “a hardcore drug addict,” says the early phase of the group was therapy, allowing him to see his own life differently. “I have a lot of provenance and pieces of paper and things, pictures of loved ones, receipts from acting jobs at ABC. Everything took me in another direction and made me feel better.”

Indeed, pictures of artifacts floods the group, and the items lend an institutional credibility and emotional resonance.