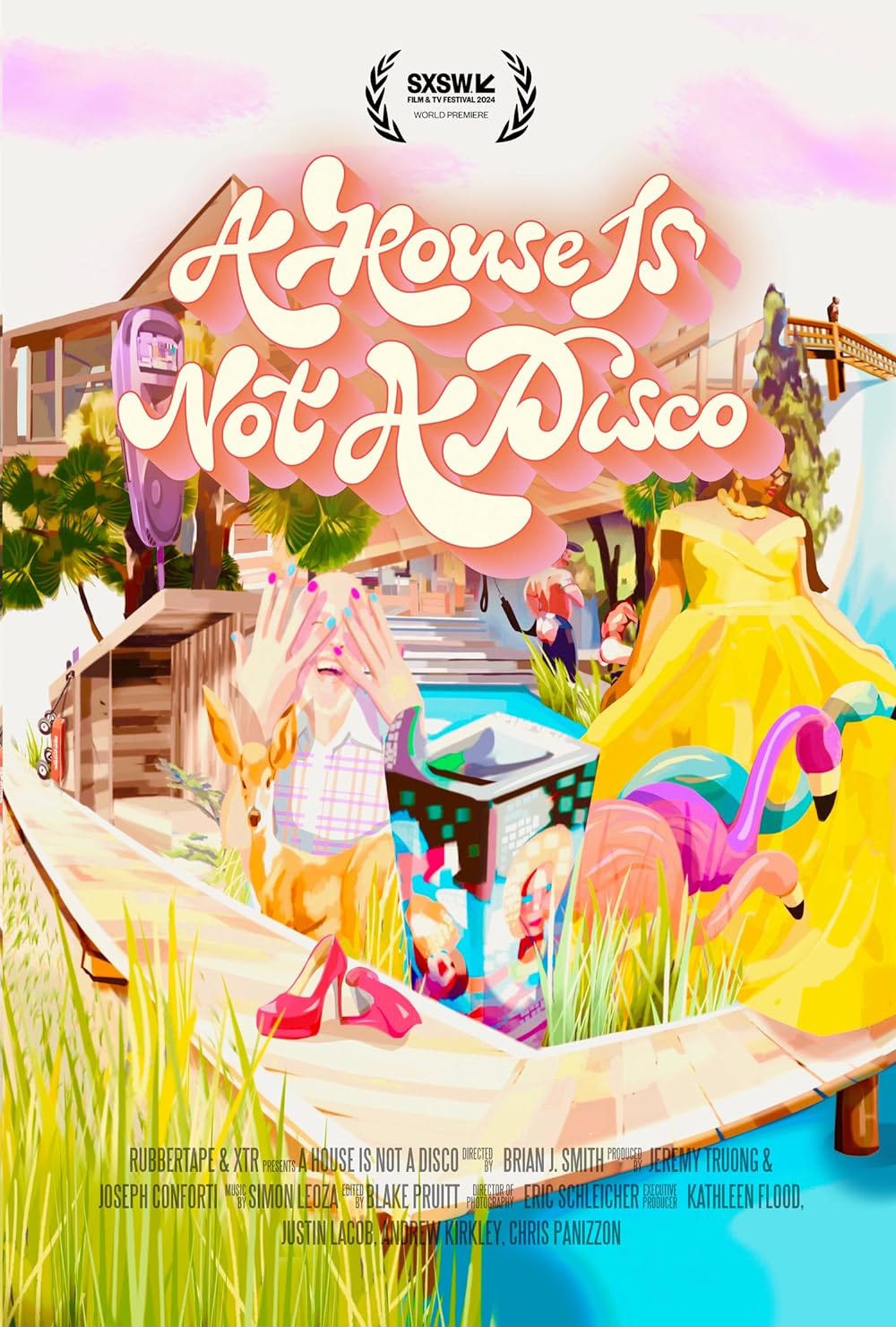

Will We Survive? An Interview with 'A House Is Not a Disco' Director Brian J. Smith

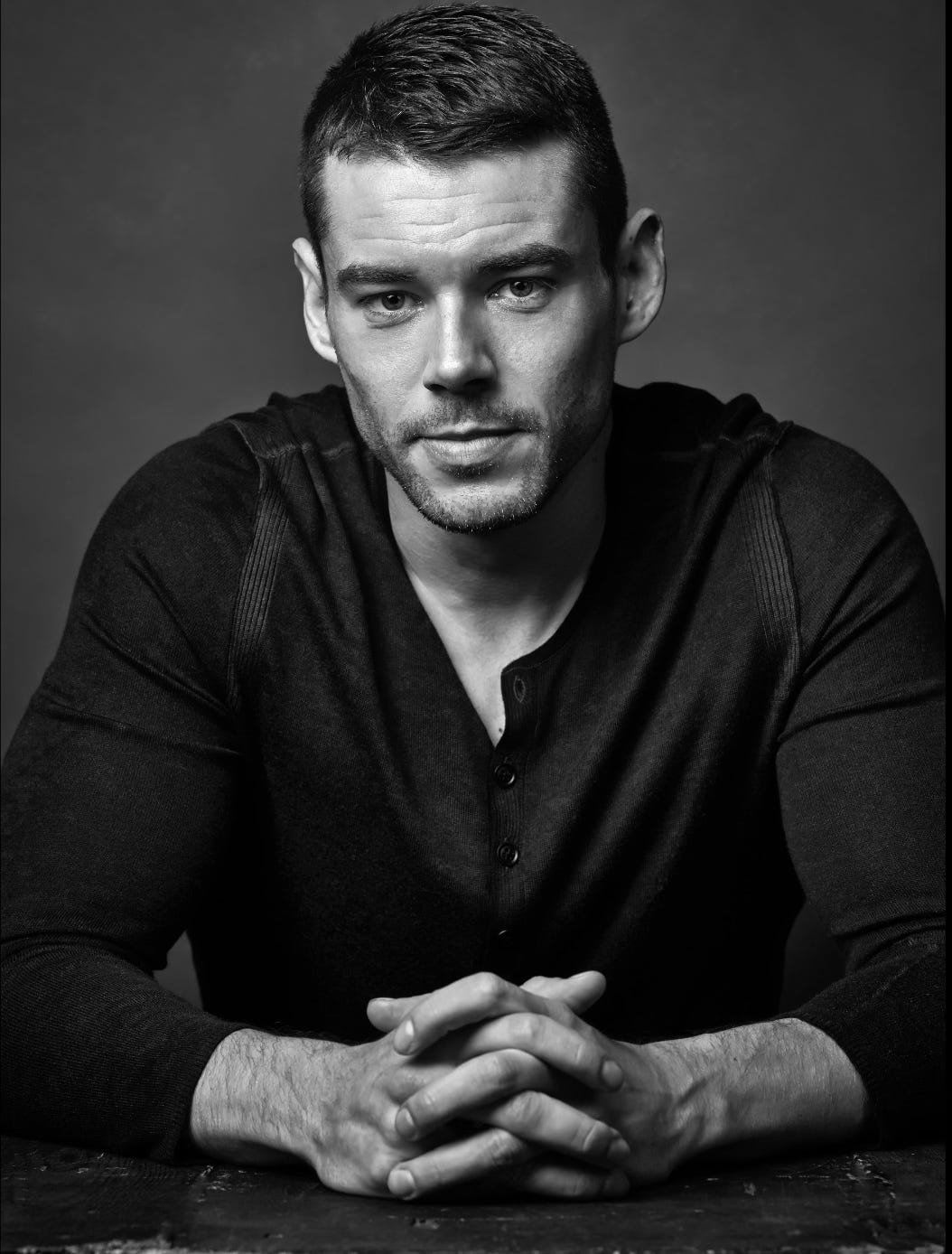

The 'Sense8' and 'Stargate Universe' Actor Opens Up About His Directorial Debut and the Threat to Fire Island as an Eternal Lure

“I could write a book about that.”

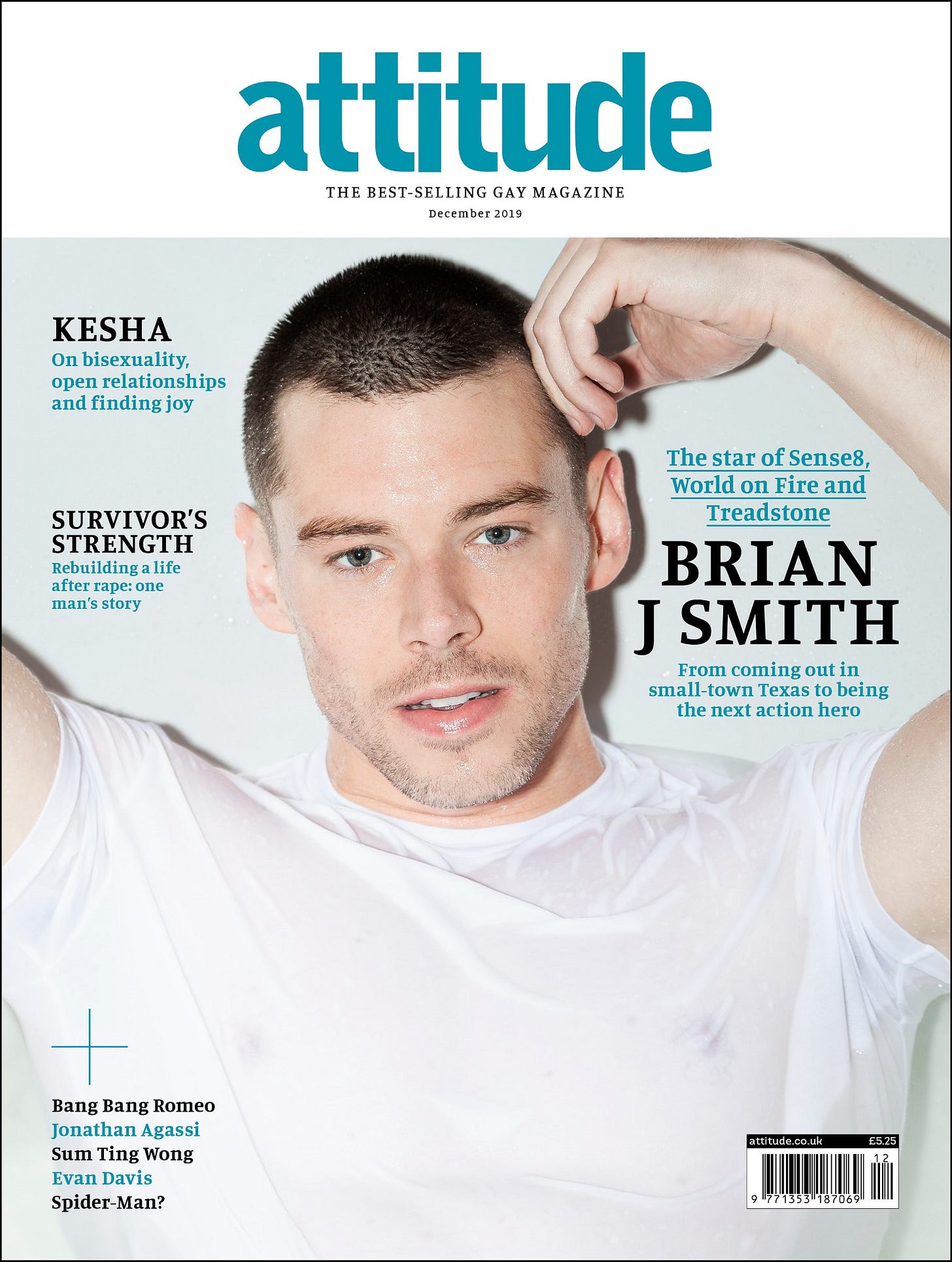

Brian J. Smith, Tony-nominated for The Glass Menagerie in 2014 and the star of the much-missed queer sci-fi series Sense8, is talking about his high-profile coming-out out nearly five years ago on the cover of Attitude magazine.

How has he found life as a professionally out gay actor? Well, it led him to become a first-time director, if that’s any indication.

“I hear people saying people are coming out because it's cool and easy and you're gonna get more work that way,” he says. “I can honestly say that I have not gotten more work as an actor since I came out, and it's not for want of trying. I've auditioned for every single Broadway play where anyone that looked like me could be in it — movies and TV series, too — and it just has not made things easier at all.”

He has no regrets, but plunging into the years-long work on his directorial debut, the Fire Island documentary A House Is Not a Disco, has filled the void. “You have to forge your own path, and I feel like for me, this documentary was an opportunity to make something and to put all this creativity that otherwise would have gone into something else… I think acting is a service industry. If you've directed or written something, it feels more personal.”

A House Is Not a Disco — playing film fests and with support from newly announced executive producers Neil Patrick Harris and David Burtka — is what Smith calls “a radically positive pastoral comedy… a movie you can put on in the background or at a dinner party or when you're low.”

The film, a loosely constructed valentine to Fire Island, does have an easy-breezy quality and eye-candy look (thanks to cinematographer Eric Schleicher), but these are deceiving: at its most effective, it is a valiant and absorbing effort to capture the place’s queer magic, the quality that makes it so vital to so many generations of gay men, specifically, and to LGBTQ+ people in general.

For one thing, Fire Island has always offered the possibility of self-renewal, as one of his subjects — a trans woman — declares. Smith, who is 42, did his own reinventing while shooting on the island, and his film argues that it’s a feature of the place.

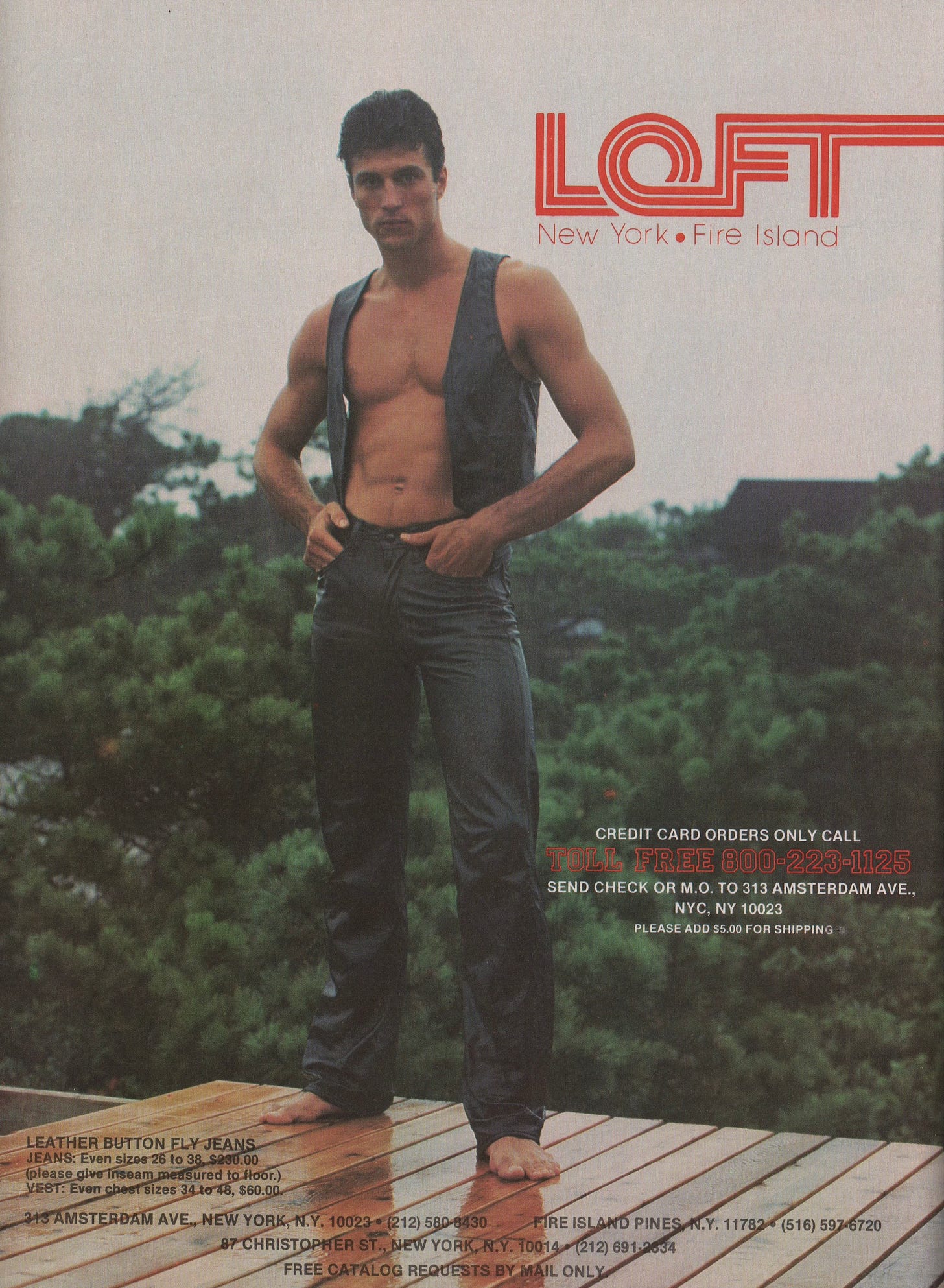

“This,” he says of the 9.6 square miles that attract so many of us year after year, “is this permissive airspace where people can go and be silly, effeminate, sexual or can experiment with drugs and partying and get their hearts broken and all this stuff. I always saw it as something to do with permissiveness. In the real word, everyone feels like this, but especially gay people: you gotta get out there and really pass and try not to offend people too much, especially now with the right reacting in a backlashy way to all the progress that's been made. There's this sense that we have to make ourselves small in the real world. The Pines is one of these places where you can be really big.”

It’s a much-needed reminder that hedonism gets a seriously bad rap.

The most propulsive aspect of A House Is Not a Disco is a storyline about the staging of the annual Pines Party, the granddaddy of all circuit parties. The filmmakers capture the work that goes into hosting a celebration pregnant with so many hopes and dreams, all on the shifting sands of an island.

“You're photographing people trying to get something difficult done, and they've got an obstacle,” Smith observes. “The obstacle was totally unexpected — beach erosion and global warming rearing its head in such an obvious way that summer. It was really exciting to film all that stuff because it was, in some ways, a hero's journey — you're watching these guys trying to get something done that’s really, really, really hard.”

In fact, this portion of the film, coming toward the end, casually introduces the frightening realization that the doc could be a visual epitaph of a place we thought would always be there.

Could the concept of Fire Island, our refuge built on sand, be nearing its expiration date?

“We really did start to see it as a time capsule, a record left behind of what may very well be in a half century a way of life that doesn't exist anymore,” Smith concedes.

“It's almost one of those things you don't want to think about, it's so awful to even consider. At one point, someone [in the film] says, ‘We could, in 60 years, be like the lost city of Atlantis. We could be a fable.’”

“When you hear someone saying that, you go, ‘Holy shit!’” Smith says. Climate change’s mantra is the opposite of Dan Savage’s famous words of support for queer youth.

“It's not getting better… it's just going to be more of a challenge each year.”

But until any eventual final act, Fire Island will continue to grow and change, as is evidenced by the film’s chronicling of the opening of Trailblazers Park in 2022. The space pays tribute to LGBTQ+ luminaries who have been underrepresented in queer culture, including Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera.

The tension between old and new is only briefly explored in Smith’s film, but it emerges powerfully in a candid conversation between two older white men, friends who are very much a part of Fire Island’s fabric. One of them is resistant to the idea that anyone could ever feel left out by the culture of the place, and the other is gently but firmly encouraging his friend to understand how some might feel unwelcome.

“I'm very grateful to the two guys in that scene, because it's very difficult to get people to be real, to risk saying something that may not be very popular, or may not be the sort of party line we're all supposed to be saying these days. I really felt like they had this conversation in an honest, open, authentic way, and they did it with a lot of respect for each other,” Smith says. “That's what I love to see in our community, is people building bridges as opposed to shouting each other down the minute they disagree with you.”

The scene crackles because, “It's heartbreaking for a lot of the older people we talked to. For them, the Pines really was this, if you think about it in context of the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s — I'm not saying it's easy to be gay or queer in any way now, but you're gonna be hard-pressed to make the argument that it was easier back then. It was a very challenging time, and the Pines really was this place where people — oh, my God, the relief they felt. You were with your kind! You were accepted and people really did reach out for you. For them — older people in the queer community in general — they hear there are people who do not feel like they've been brought into the fold, the reaction is less, ‘I disagree with that, I don't believe that,’ and more like, ‘I can't believe that's happening?!’”

It’s a potent subject, with our community debating the use of the word “queer,” the concept of gender and even which version of our unofficial flag is most legitimate.

“How are we, the most heartbroken people over not having our own proms and not being able to come out, how did we turn into this community that's debating about how exclusive or inclusive it is?” Smith points out.

Summarizing the push and pull between Fire Island’s old guard and its newcomers as a metaphor for our community at large, he labels it a matter of, “How did we get here?”

Now that Smith is here, at the beginning of a new direction in his career, he’s going with it, and A House Is Not a Disco is a deeply personal start, which is always the best kind of reinvention.

“There are parts of me in this movie that I can't even explain to you. I learned a lot about my blind spots and the things I was good at that I didn't expect to be good at. This is much more fraught [than acting]. Even though I'm not in it at all, I feel like I'm more exposed in this than ever.”