The Memory of Roy Blakey

Your chance to help a doc, "Uncle Roy," capture a gay artist's unique legacy as a photographer and ice skating archivist

April 20, 2025

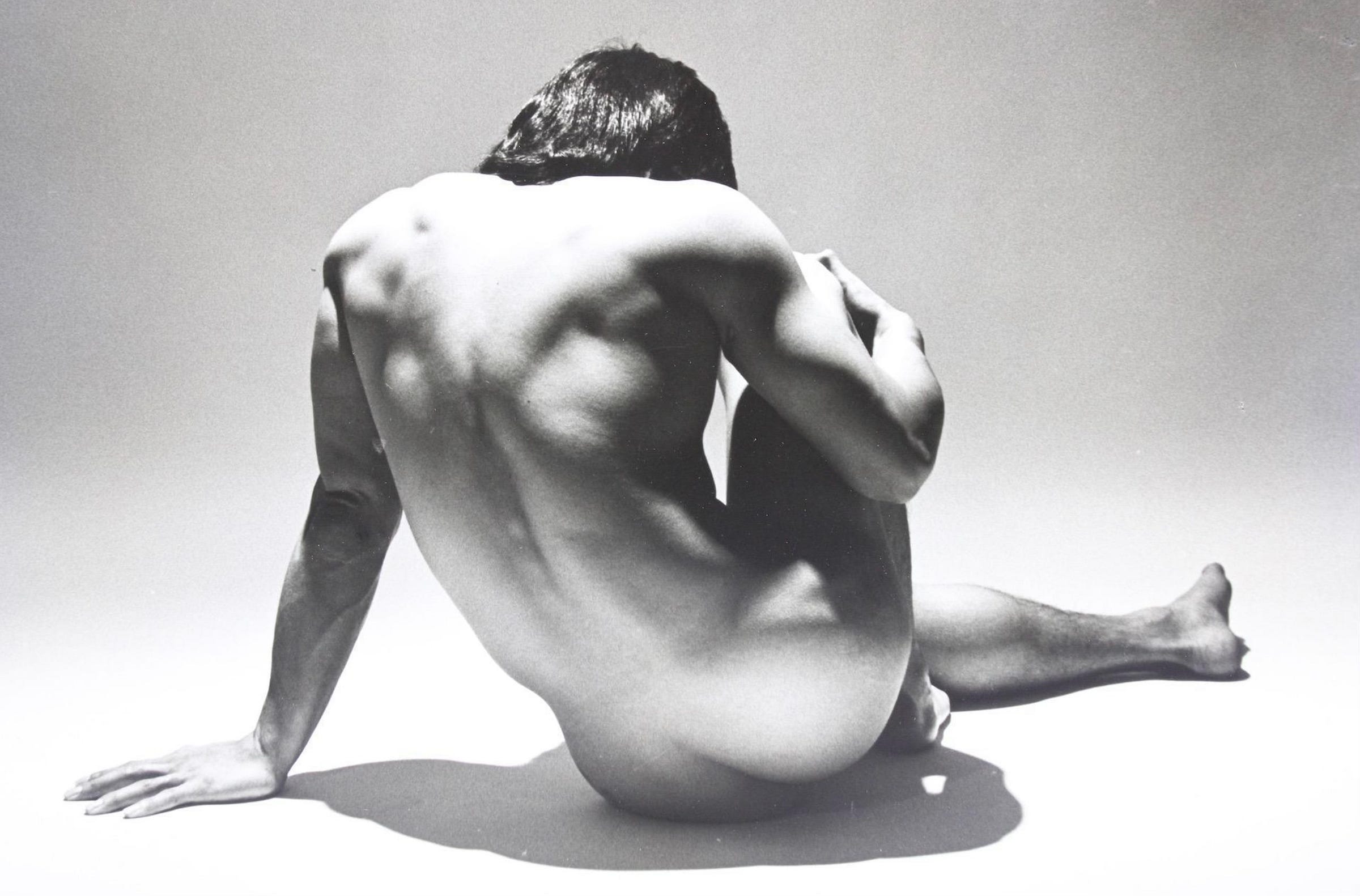

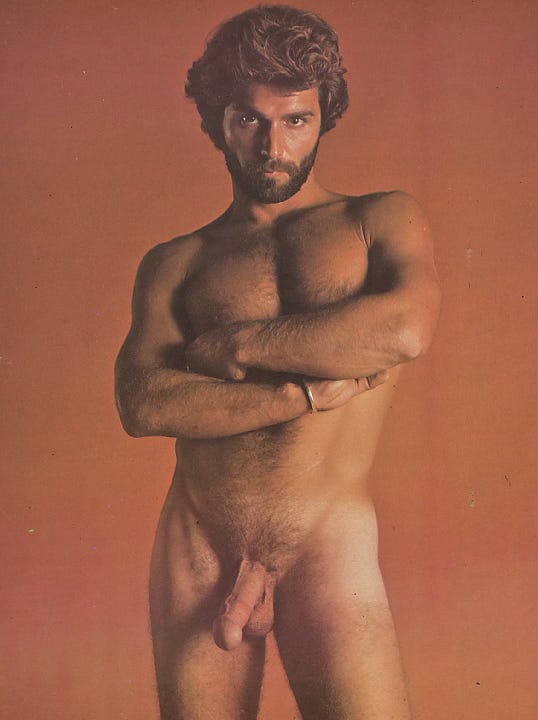

Last year, when photographer Roy Blakey died at 94, I posted an appreciation of his work. Though he often led with his status as the world’s leading archivist of ice skating memorabilia when talking about himself, Roy was an important photographer of celebrity portraiture specializing in the world of dance, and a tremendously skilled shooter of the male nude who prefigured Bruce Weber.

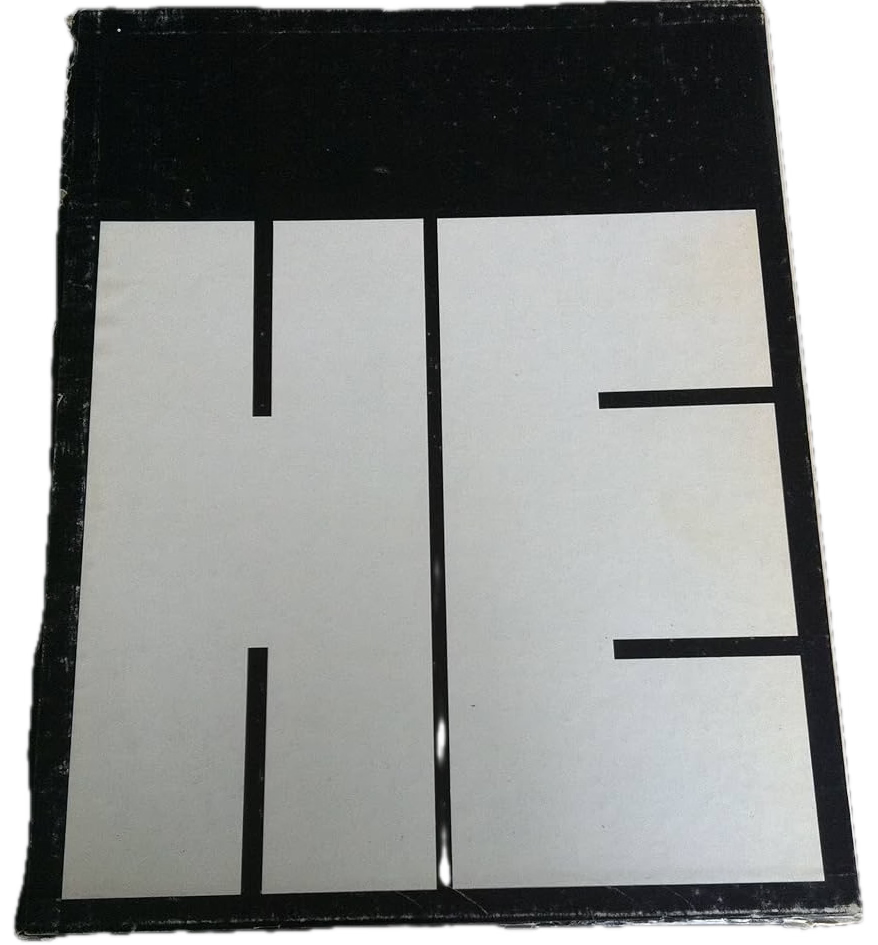

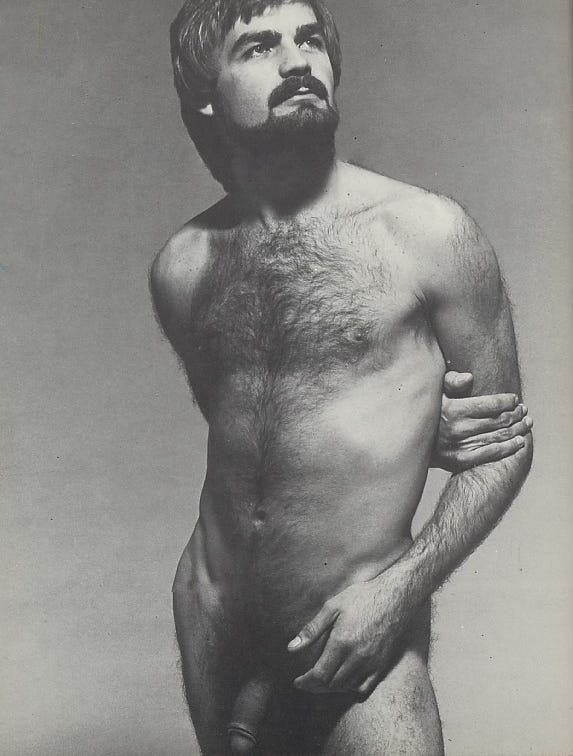

In spite of being far from a Gay Lib activist, Blakey took the remarkably brave step of publishing a book of his male nudes in 1972. Entitled He, the book has been called the first book of its kind that could — thanks to a series of court decisions — be mailed legally using the USPS. Not too many years before, photographers were raided and their lives and livelihoods ruined over something as common as owning a pet is today: taking pictures of naked men.

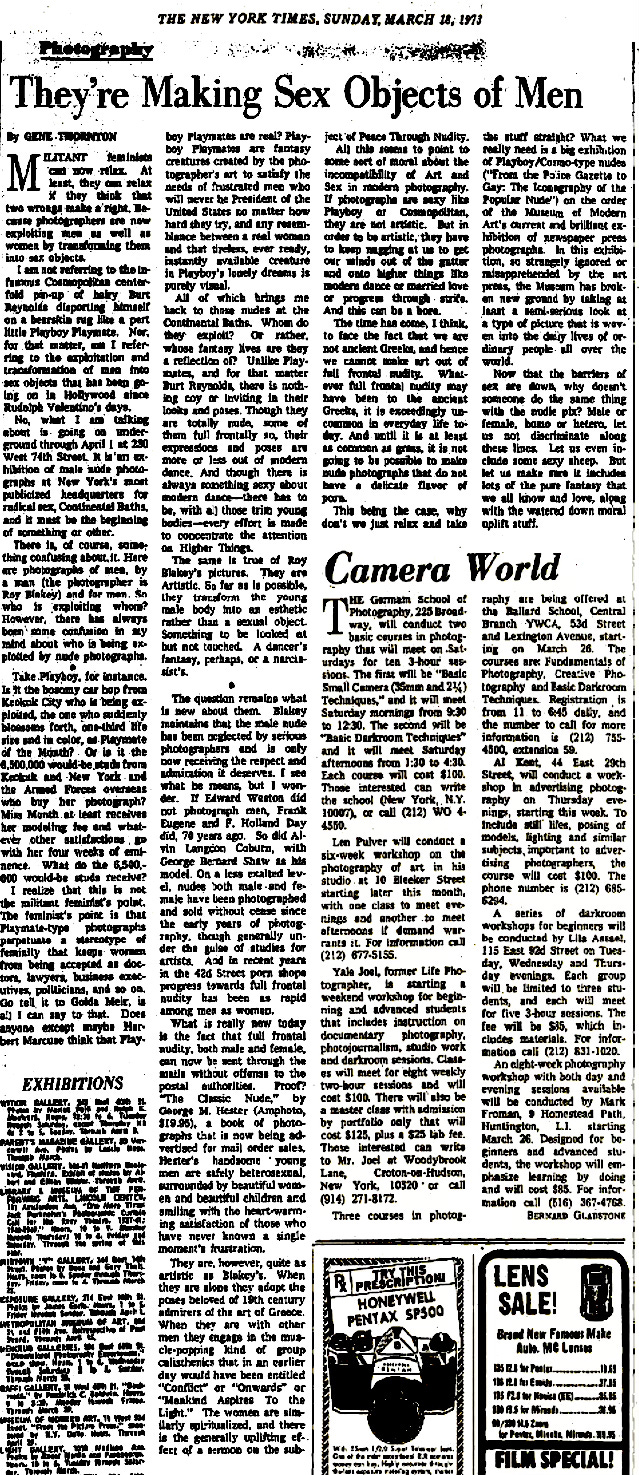

Even the liberal New York Times had a heaping helping of snark for Roy’s trailblazing imagery. In its March 18, 1973, edition, its photography critic Gene Thornton turned in a piece entitled, “They’re Making Sex Objects of Men.”

In it, he wrote:

“Militant feminists can now relax. At least, they can relax if they think that two wrongs make a right. Because photographers are now exploiting men as well as woman by transforming the into sex objects.”

He was reacting to an exhibition of Roy’s photography at the Continental Baths, and couldn’t resist such homophobic tropes as suggesting they depicted “narcissism,” noting, “Here are photographs of men, by a man … and for men,” and asking, “Who is exploiting whom?”

Of course, Blakey’s work showed what the photographer already knew — men aren’t exploited when they’re photographed, and don’t need to be made into sex objects by a camera. A photographer doesn’t have to work at elevating a subject’s characteristics to make them sexy. If Roy found a model sexy, so did his camera.

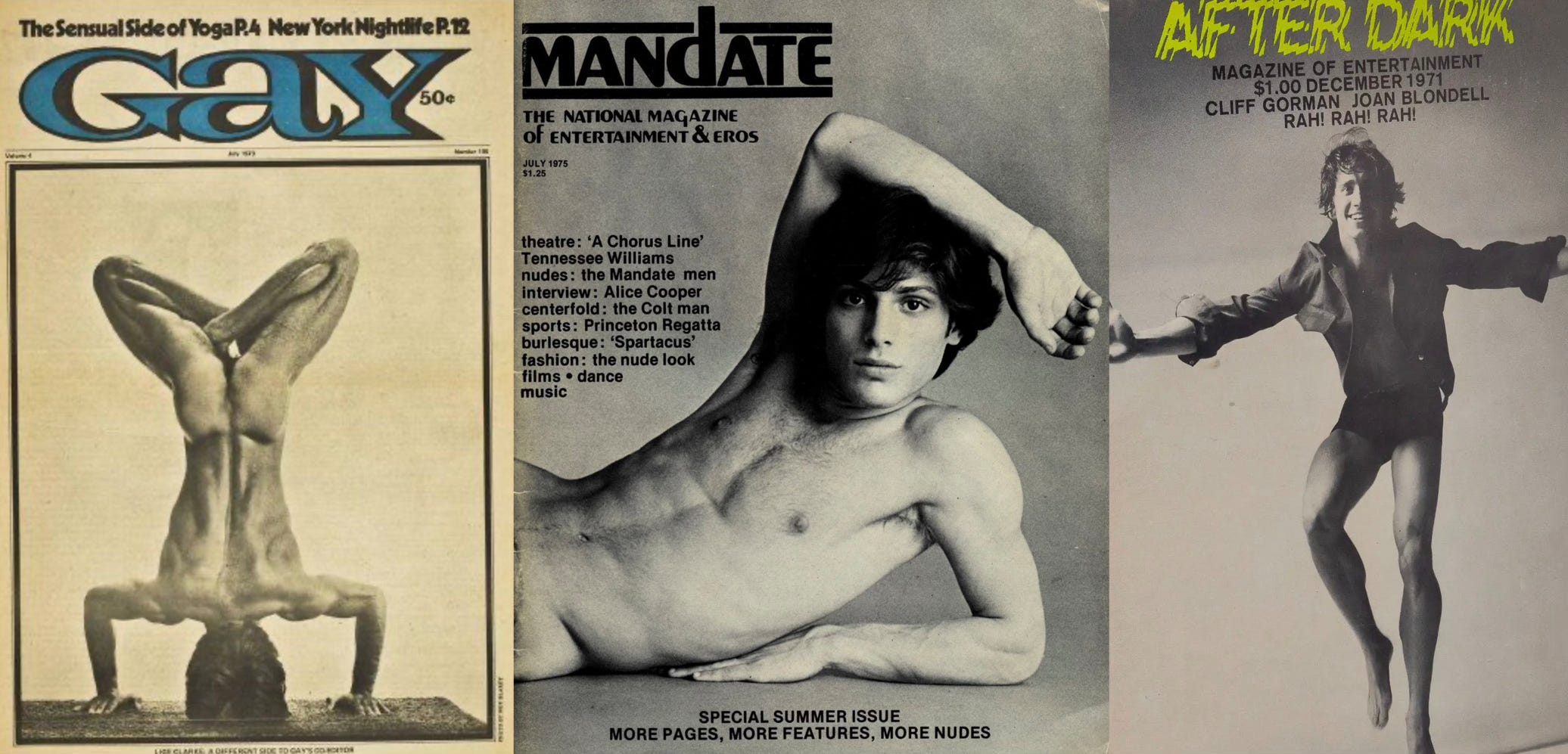

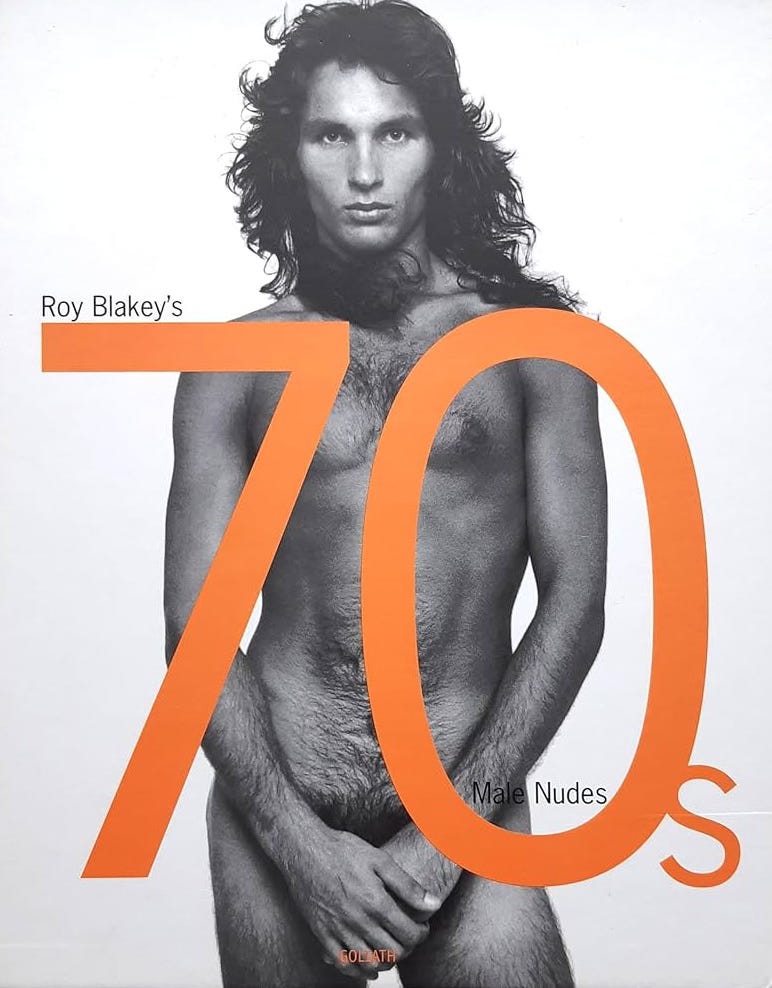

Roy continued shooting for a couple more decades from his Chelsea NYC studio, publishing with After Dark, Mandate and others, eventually retiring to Minnesota. His second book, created with the help of close friend Reed Massengill, was Roy Blakey’s ‘70s Male Nudes, published in 2002.

Now, Roy’s niece Keri Pickett, who directed The Fabulous Ice Age (2014), is seeking completing funds for a doc devoted to her uncle and his work. Uncle Roy promises to document his one-of-a-kind ice skating treasures, his physique photography, his niece’s race to find the right institution to acquire his life’s work as well as his battle with dementia.

I spoke with Keri and the film’s producer Dawn Mikkelson by Zoom last week about their Kickstarter drive — invest HERE.

Keri, when did you first realize how special your uncle really was?

KERI PICKETT: Well, he started piquing my interest as a little girl when he came and visited us at Christmas time, and he gave me that photograph of himself. And I’ve got to tell you, I kept that photo on my dresser all my growing-up years, even though I really didn't know who he was. He was off traveling the world, and I really did not have any clue what that clown picture meant. I was like, “Is he in the circus?” I really didn't know, but I think it made me wonder, and I probably made up some stories about him.

And then he came to Minnesota again once, for my my grandparents’ 60th wedding anniversary, and so I got to know him a little bit better then. Short visit. And then when I was in college, my photography professor said, “Keri, you have too much energy for this place, you have to go to New York City.” And so I thought, “Well, Roy lives in New York City.” And even though I didn't really know him very well, I asked him if I could stay with him at the beginning of my journey moving to New York City to try and become a photographer.

He let me stay with him for two weeks, and then he kicked me out because I was tying up his phone line and he couldn't get any business!

Did you even know he was a photographer at that time?

KERI PICKETT: I did. My grandmother took me on a trip and I got to see his studio when I was 11 or 12. I do remember seeing the portraits and pictures — portraits and pictures of people in midair, frozen in midair. And I really wondered, “How does he do that? How does he make them?” I felt that his pictures were like magic. I think it planted a seed, but I was really young, and so I don't know. But his existence as a professional photographer enabled me to know that it was possible to be a photographer.

For each of you, what does Roy’s work say to you?

KERI PICKETT: I think that Roy really was somebody who appreciated beauty and elegance, and he surrounded himself with artistry. His home was filled with art and artistry. And I think when he set out to do personal work, that was at the heart of his mission. And so dance, definitely interested in him. And so you can see that influence of dance, even in people who are simply standing or just presenting themselves as very non-jumping or in a normal way, you'd say. You can see the artistry in just his lighting and in the moments that he captured. And I think the pictures are classic, but they still have a deep resonance, an emotional resonance.

DAWN MIKKELSON: I am less of a connoisseur of photography. I'm learning a lot through editing this film, but I would say that his attention to lighting is very unique and beautiful. And I also I think that there's something to be said for, as Keri was talking about, his commitment to beauty, but also each of these people are so individually beautiful, and somehow he's able to pull out their uniqueness in their beauty. And so it is a Roy picture because the people in the photo are uniquely themselves and uniquely beautiful.

I agree. Even when he has a lineup of beautiful boys, it doesn't just look generic. It does feel like individual portraits. There's not a driving sexual element to it, so I was wondering at what point, Keri, you realized he was a gay man? Was there a conversation?

KERI PICKETT: I just deduced it. I shared it with my mom in the early ‘80s. I'm like, “Mom, did you know that Roy is gay?”And mom was like, “What?!” And she'd been staying with him when she had business in New York. My presence in New York also helped my mom get a firmer grasp on her friendship with Roy. And that started a deeper adult relationship. But I don't think that it's revealed in the film that I had to really get it out of him. It wasn't something that he wanted to talk about. I remember seeing Blaze Enterprises on his doorbell in New York City, and I would be like, “Why doesn't he talk about Blaze Enterprises with me?” And so I did know about some of the magazine work, but I think I really found out much more about the of the magazine work after I started talking with people about Roy's photography. And I heard from so many people who said, “I lived in rural Minnesota, and I subscribe to After Dark, and Roy Blakey's pictures always stood out for me and helped me feel like my love of these pictures was given a stamp of approval by Roy's artistry.”

And then the beauty of the pictures in the '70s is, too, that people's approach to their own bodies and their own being was much more natural. It was okay to be hairy, everybody didn't have to have six-pack abs to be in his pictures. It was really about just celebrating the body beautiful, but not just one type. I mean, I'm not saying that all the men don't look real good, because they are really beautiful men.

It's interesting that he comes from the generation where they didn't announce their sexual orientation, and yet he published an early book of male nudes which is pretty radical.

KERI PICKETT: Well, he didn't really speak about it. Reed Massengill came to Minneapolis and saying to Roy, “You influenced my life. You helped me become a photographer of male nudes, and I consider you a VIP elder in my world.” And then he helped him publish that second book, Roy Blakey's 1970s Male Nudes, and they had a different edit. He brought a different eye. That book was published in 2002. Reed really encouraged Roy to get into the dark room. And Roy's mastery of the printing process advanced. When I look at some of the vintage prints from the 1972 book, He, and I look at the prints from later on, I think that his printing got better for that second book, and his artistry got better.

Getting into Roy's archive and getting deeper into it, I always knew that he took a class at the Ansel Adams Workshop out at Yosemite. Ansel wasn't there at the time, but he worked with Jack Welpott and so many people. But one of the other people at the class was Eikoh Hosoe, a very important Japanese photographer, who helped encourage Roy to go ahead and not be afraid to do full-frontal nudes. I think Roy needed some encouragement to go ahead and just focus on men. I see his pictures from the workshop. I know that that was the famous workshop where there were tons of important photographers there, and I only really see him focusing on the male nudes. There were important women models there at the time as well, and so his interest was really strong right away, but he did need encouragement. And I think it was a process for him to go ahead and say it's okay to do nudes and include the penises and include everything and just be straightforward and not be worried about how people will respond.

[Editor’s note: Coincidentally, Hosoe and Blakey died within about a month of each other last year.]

It's very natural approach. Also, I'm making the connection to the ice skating. That's also a thing that is an exaltation of the body. Did both of you get a chance to see his whole archive of ice skating material?

KERI PICKETT: Well, I've lived with it because he and I share a photography studio. It was all in the building. I don't live in the building, but I work in the building. And so this togetherness in the studio helped me appreciate the importance of his collection because he would have so many VIP guests coming to see the archive and visiting, groups of skaters, but then also people like Dick Button and Brian Boitano. And when the world championships were held in Saint Paul, Roy had a big party, and the who's who of theatrical figure skating was in our building.

What did it physically look like? Was it just like Citizen Kane? It seems like he had everything.

KERI PICKETT: He had everything. He had costumes, posters, programs. All the posters he would send to New York City to a firm, two guys that were so brilliant at restoring posters and then putting them on linen. He had all of his posters put on linen to the cost of almost $1,000 a poster.

He had hundreds of posters, and he had them all put on linen. I mean, he was so dedicated to his archive and his history and the beauty of these pieces. He really helped preserve them for generations and generations to come. And so, I knew that it would be important to know where his archive would be going. In part, I did the movie The Fabulous Ice Age in order to help with the express desire that I would help Roy find a place for his more than 44,000 pieces, because he really kept going and buying right up until the very end of his life. But I knew it would be important to find a place for that. This effort to find a home for his archive is also one of the main story arcs in the film.

That's a major attraction point for me because I'm a big collector of things. I understand the concept of going and going and going. I always wonder, especially as you get into your 50s and older, what is the end game? My understanding is Roy’s skating and photography archives both ended up in the same place. Is that correct?

KERI PICKETT: Yes, they did. Roy and I, after all these years, we could never have dreamed up how it was all going to go. It was a shock and a surprise to us as well. And then the way that it all unfolded, it was really on me to find a home for that archive because Roy didn't really want it to leave him. He couldn't bear the thought of it going anywhere else. He wanted to keep it close to the very last minute. And I don't blame him. I mean, he started collecting when he was 10 or 11. Many, many decades of this defining his movement forward in the world. It takes money to hold an archive. It takes archival materials, insurance, people to handle it, a registrar, a way to log it all in and to hold it. And we found through the years that there were a lot of places that wanted only parts of the collection.

You could have sold things off one by one.

KERI PICKETT: I could have sold things off one by one. The Sonja Henie costumes are incredibly valuable. He didn't want it to be broken up. And that's the goal, is to preserve his vision of this history, which was so thorough and so incredibly impressive that it was too big for anybody to take in its state.

One gay person in this world has done something that will be remembered for generations to come.

Do you hope Uncle Roy will capture Roy's identity and be his legacy?

KERI PICKETT: For sure. Roy is revered in communities that know what he has done. But I think part of the thing that's revealed at the end of the film, and we see even in the sizzle wheel, is that it really reveals the impact of just one person's life. One gay person in this world has done something that will be remembered for generations to come. And I think that's really valuable, especially — I mean, always — but, you might say, especially now.

For each of you, do you have a favorite photograph and also a favorite piece of his collection that you've encountered?

KERI PICKETT: I've often wished that I was 40 or 50 lbs. lighter so I could fit into some of those little sparkly numbers, just to try them on just for a minute. I put on the tiaras and stuff when possible. But I would say he's got this one vest that's made of crystals, and the tiny little vest must weigh 20 lbs. because it's full-on real crystals. At one point, he had it hanging and the sun hit it, and it threw rainbows all over the studio.

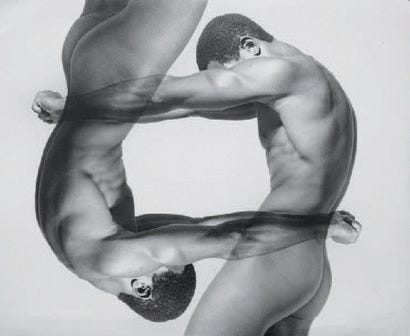

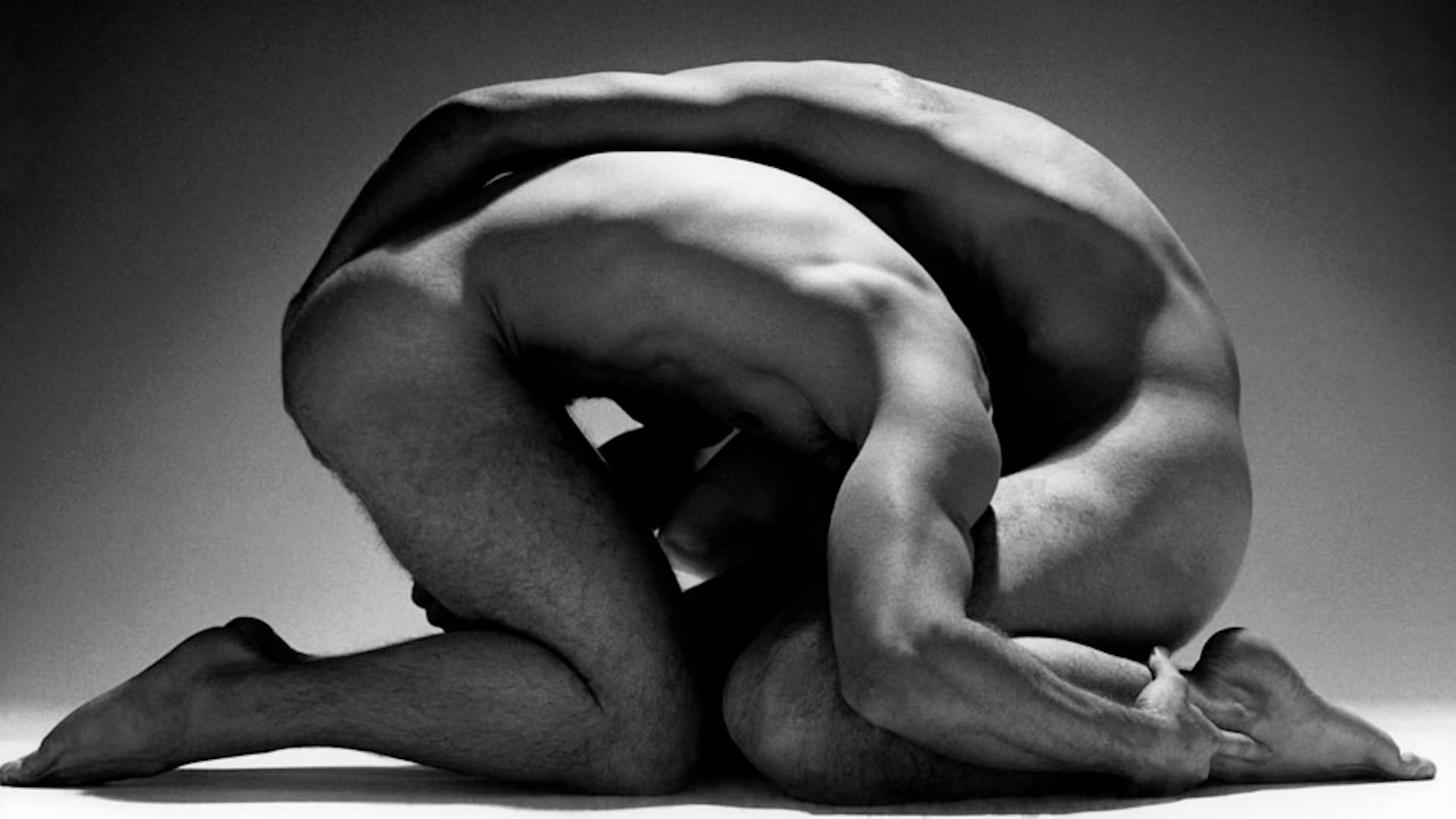

And there's one moment in the film where he says, “This is my favorite photo.” And I think, in a way, he influenced me, and that picture has become a big favorite for me, too. And it's an image from behind of two men, and you don't see their faces, you see their backs, and their legs come down, and their feet are touching one another.

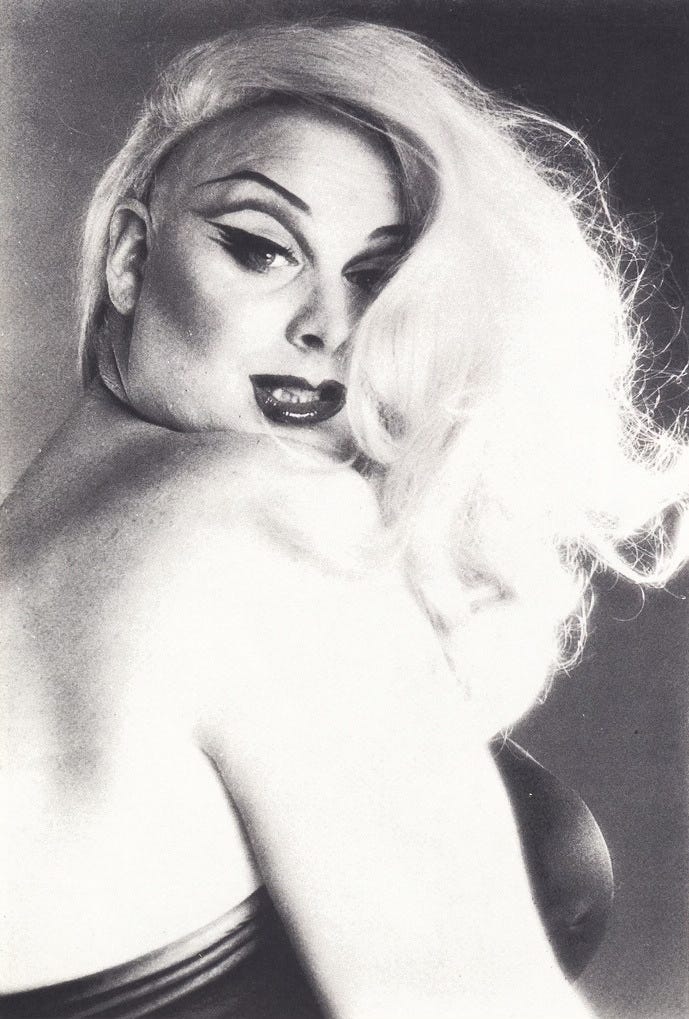

DAWN MIKKELSON: I'm thinking of that one where they're wrapped around each other. You can see that on the Kickstarter page. It’s like, where does one person begin and the other one end? It's just beautiful. I will also say that his work with queer icons. We don't get it too deeply in the film, but we do go there. And there's some photos of Divine that are amazing. They are divine, and they so capture that character. And so, again, we’re back to this whole thing about Roy knew how to really capture the essence of a person. Those are my favorites.

Toward the end of his life, he developed dementia. I've thought a lot about that because I think with queer people, there's a special consideration of, “Who's going to take care of me?” And I wonder if you could speak a little bit about that and also about what his last years were like. When I spoke with him a few years ago, he seemed confused but … happy?

KERI PICKETT: I think that can be attributed to his basic upbeat nature. His parents are introduced in the film, and they set the tone for our whole family for being interested in history and education. And his mother set the tone for humor and being happy. He was really a very happy person. And even though the dementia started maybe a couple of years before it became really front and center, it just ebbed and flowed in the background, and so it wasn't until ... I think he might have had a seizure once before, and I missed it because I came in and I saw evidence of something, and I brought him to the hospital, and they couldn't find anything, but I could see that there was evidence of an incident of some kind. And so I just happened to be at his home for a life-threatening situation. And so then, that changed everything much more quickly, set the final stage of him living with this. Dementia has many, many forms, I learned. But one of the things I did learn also is that I do believe there's special consideration when having elder care for queer people.

Roy didn't necessarily need it, but when a young man would come — I did get a service to help relieve me sometimes — I always noticed that they were both just so happy to hang out with one another. And the women were happy and loved him, too. But I do think Roy had a special response to the young men who came, and maybe he felt a little more comfortable. I don't know. I think that there's an opening in the marketplace for queer elder care. ⚡️

Poika kultturi