Life's Work

Photographer Lon of New York and the Rebirth of Beefcake — A Vintage Interview from 1997

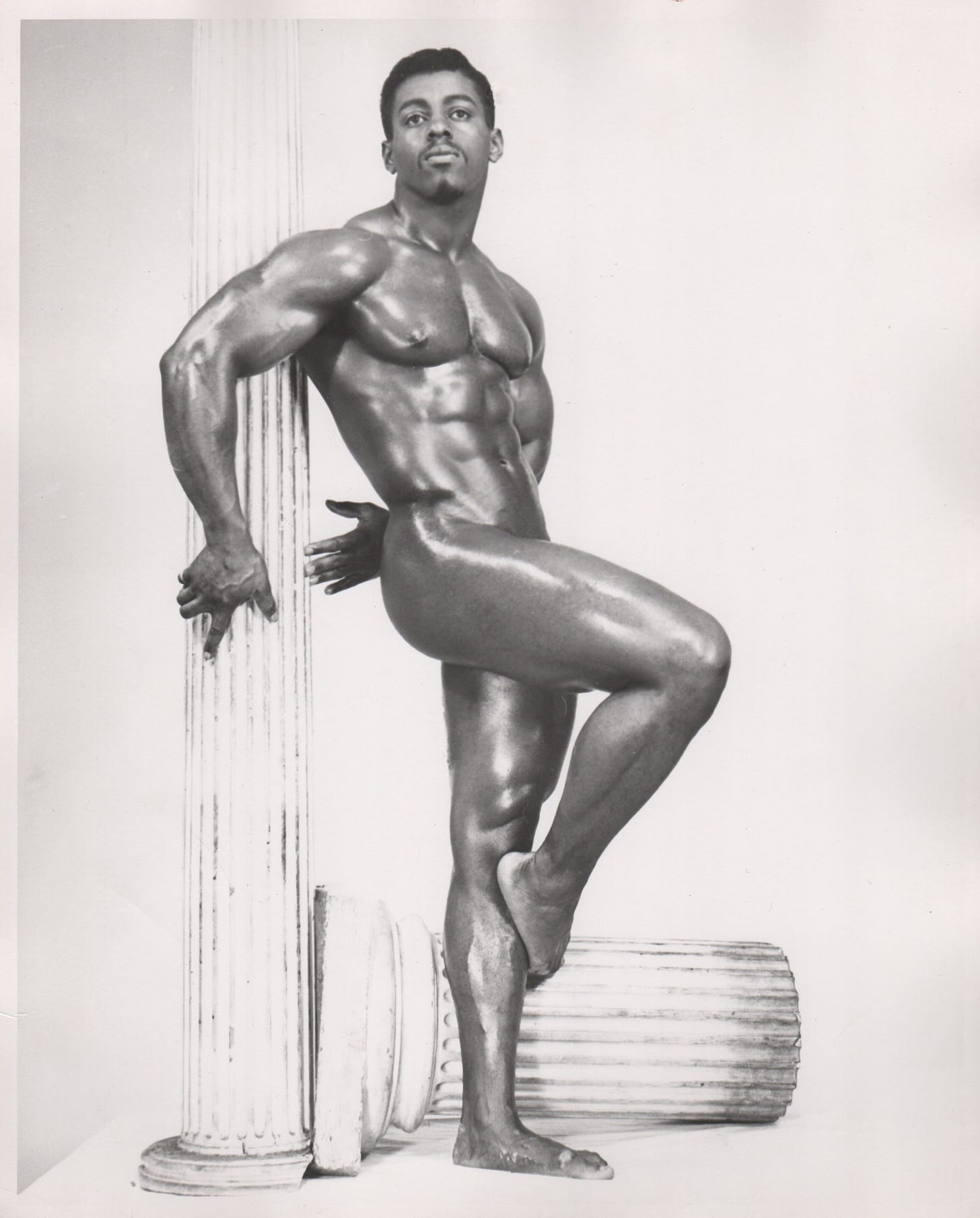

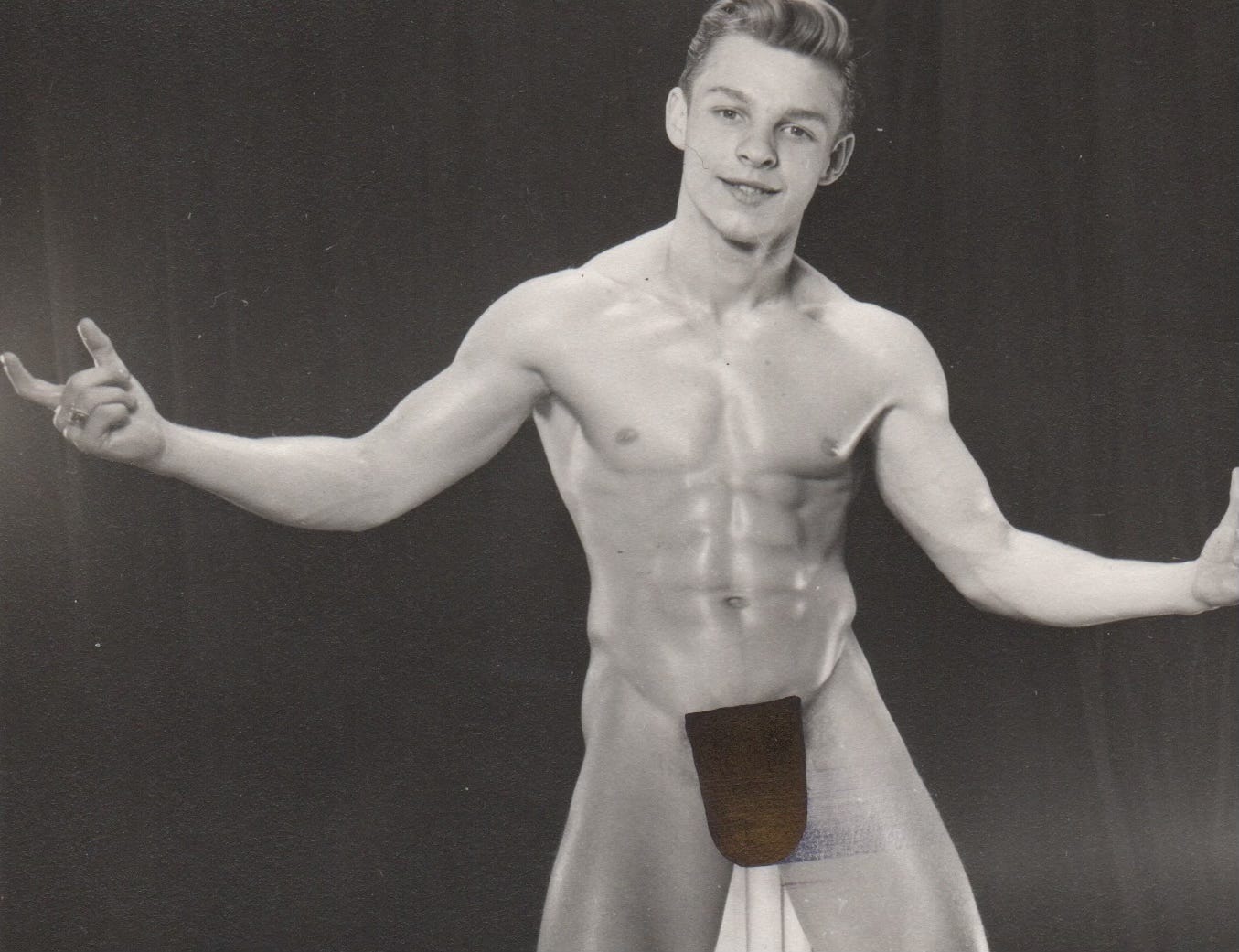

More than 25 years ago, I received a review copy of a new book published by Janssen Verlag called American Photography of the Male Nude: 1940—1970: Lon of New York. It was the second in the series, sandwiched between Bruce of L.A. and Dave Martin, both photographers with whom I was very familiar. (There were later at least five more published — Douglas of Detroit, Pat Milo Al Urban, Bob Mizer and Peter Berlin.)

I'd never heard of Alonzo Hanagan, but the book was beautiful, full of classic male nudes in a variety of shades, a departure from more physique photography, which was overwhelmingly white-oriented.

I’d always wondered about that period of photography — and of gay history — considering that so many of the muscle-bound posers were ostensibly straight, or what passed for it back before gay rights drew a necessary line in the sand. If it was terrifying to be gay back in the day, what drew so many men who probably did not ID as gay, first and foremost, to pose nearly or totally nude for gay mens’ lenses and eyeballs?

Not to mention what went on when the photographer put the camera down.

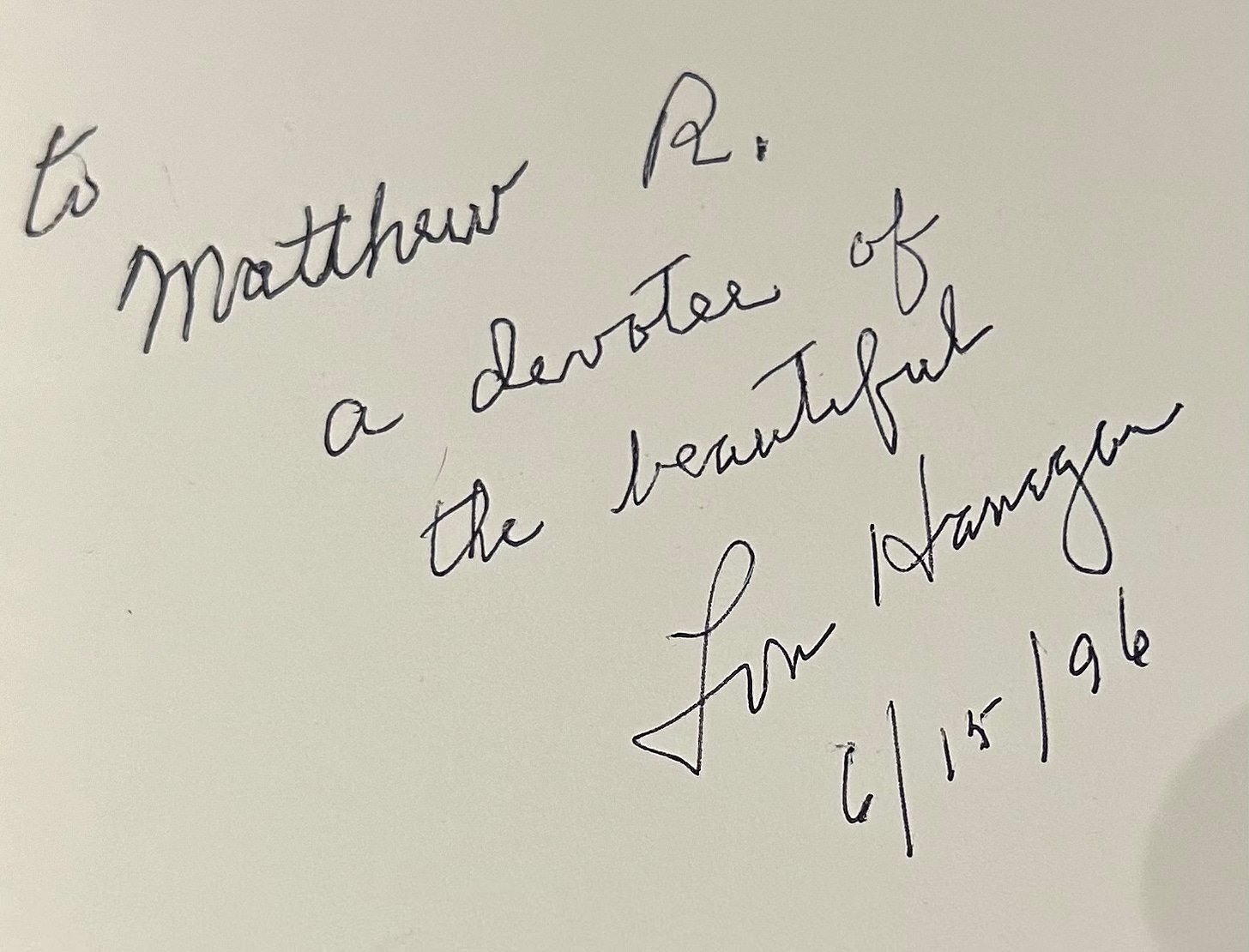

When I realized Lon was still alive and residing in New York (in Mae West's old digs ... get her!), I requested an interview, never dreaming he’d say yes. He said yes and I dutifully showed up at his brownstone, where I found him to be somewhat the worse for wear but still kicking — and with the memory of an elephant. Lon was in boxers and a robe and not terribly mobile. I was scared to death audiotaping him because in those days I had an analog tape recorder that worked on sound, so as a small voice drifted out of the large man, I was desperately hoping I would not lose his words.

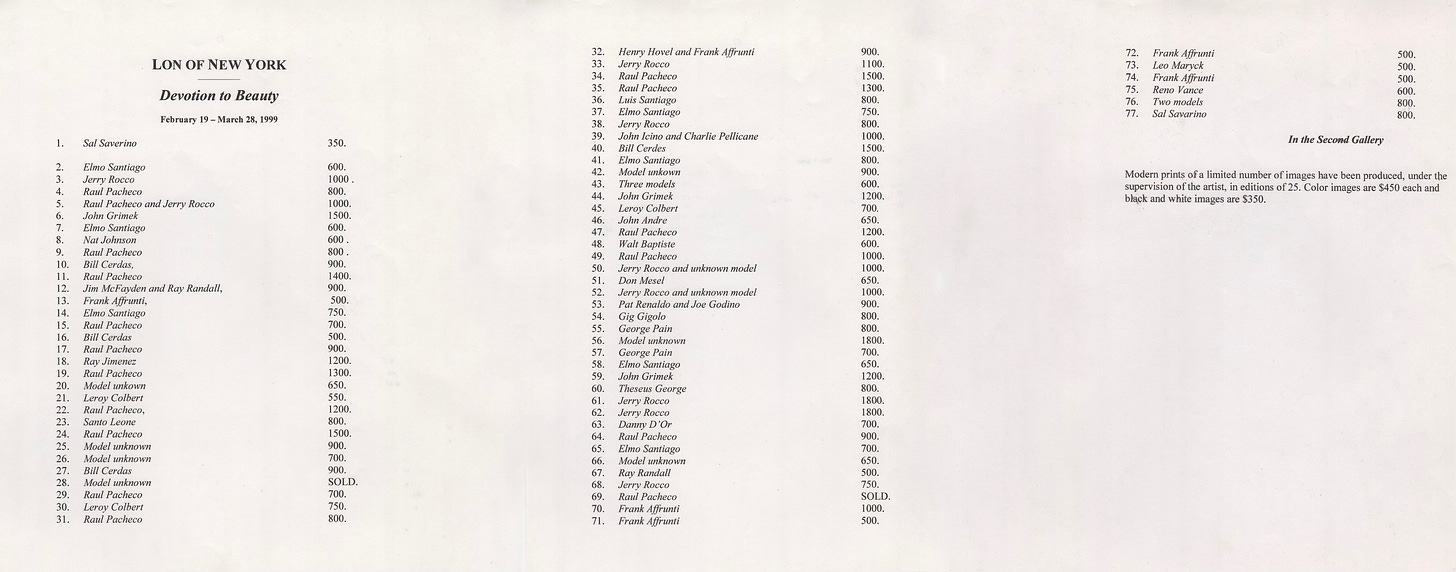

Lon’s caretaker/peer/friend told me he was going back to photography, and in fact he did show at Wessel + O’Connor in 1999. I can’t imagine his 1990s works could truly be attributed to him — he just didn’t exhibit a coherent, creative spark when I spoke with him — but he was certainly indomitable.

I published the interview in an issue of Torso, and I understand Lon was very pleased with how I’d framed his story. Chatting with him felt like a rare opportunity to get some insight into a lost time about which I’d had a lot of faulty assumptions — for one thing, he was not at all enthusiastic about “Gay Libbers.” Hmmm. I guess the gay-rights advocates alienated all the trade.

But, as I think we all now better understand that different generations view “progress” differently, he was nonetheless heroic as an artist and as a gay man in that he openly practiced his art and his commerce, dealing with prison and harassment.