Fred Bisonnes, Beefcake King, Bares All

A career-spanning talk with DENNIS FORBES, the multi-talented "homoeroticist" behind the brand that helped teach us what's HOT.

Dennis Forbes may have photographed more men more erotically than anyone else during the Golden Age of Gay Porn.

But who is he?

He's better known — but still not widely known enough — as Fred Bisonnes, whose vision of the male form became one of the most dominant in gay fantasy history, thanks not only to his running Western Man publishing in the '70s and '80s and his founding of Advocate Men in June 1984, but to his being involved

with so many other publications, businesses and creators, starting more than 50 years ago: After Dark, Vector, The Advocate, Jim French, Kristen Bjorn, Crawford Barton, Kenn Duncan, Chuck Holmes, John Preston, Modernismo's Mandate and Honcho, and many others.

He shot everyone from Christopher Isherwood to Peter Berlin, Casey Donovan to Bill Henson, Al Parker to Leo Ford — and in many cases produced the very images you think of first when you hear those names. He built on Colt's image, and he revamped Falcon's, putting his personal stamp on both.

In short, the Fred Bisonnes aesthetic was a cock ring around the entire scene.

Because this Renaissance man — who had been in the Navy, attended Brigham Young University, at one point looked like a hippie and worked as a copywriter for Better Homes & Gardens— wore so many hats, he wound up having had an impact on gay culture far greater than he might have as merely another gifted photographer. He was a writer first, he became an illustrator, he created collages and he was a one-man packager as well as a freelancer.

Through it all, Forbes's eye for beauty, his taste level, and the decisions he made about what he would not do at a time when many others were happy to do whatever they were asked, to the detriment of making anything lasting, established his own unique style. You can tell his work a mile away — or from a distance of nine or so inches. His men are natural stunners with timeless expressions.

Even when the same models are drenched in '70s clone trappings or '80s California-twink couture in other, contemporaneous photographs, you'd be hard-pressed to find a camp Bisonnes spread.

His men look the way he saw them, and they are still as immortal as his legacy should be.

Most surprisingly, Forbes documented this casual beauty largely in a time when gay men, including many of his subjects, were dying. At the time a visual relief, the images today are also a testament to defiant self-love, sexual expression and even community amid suffering, oppression and death.

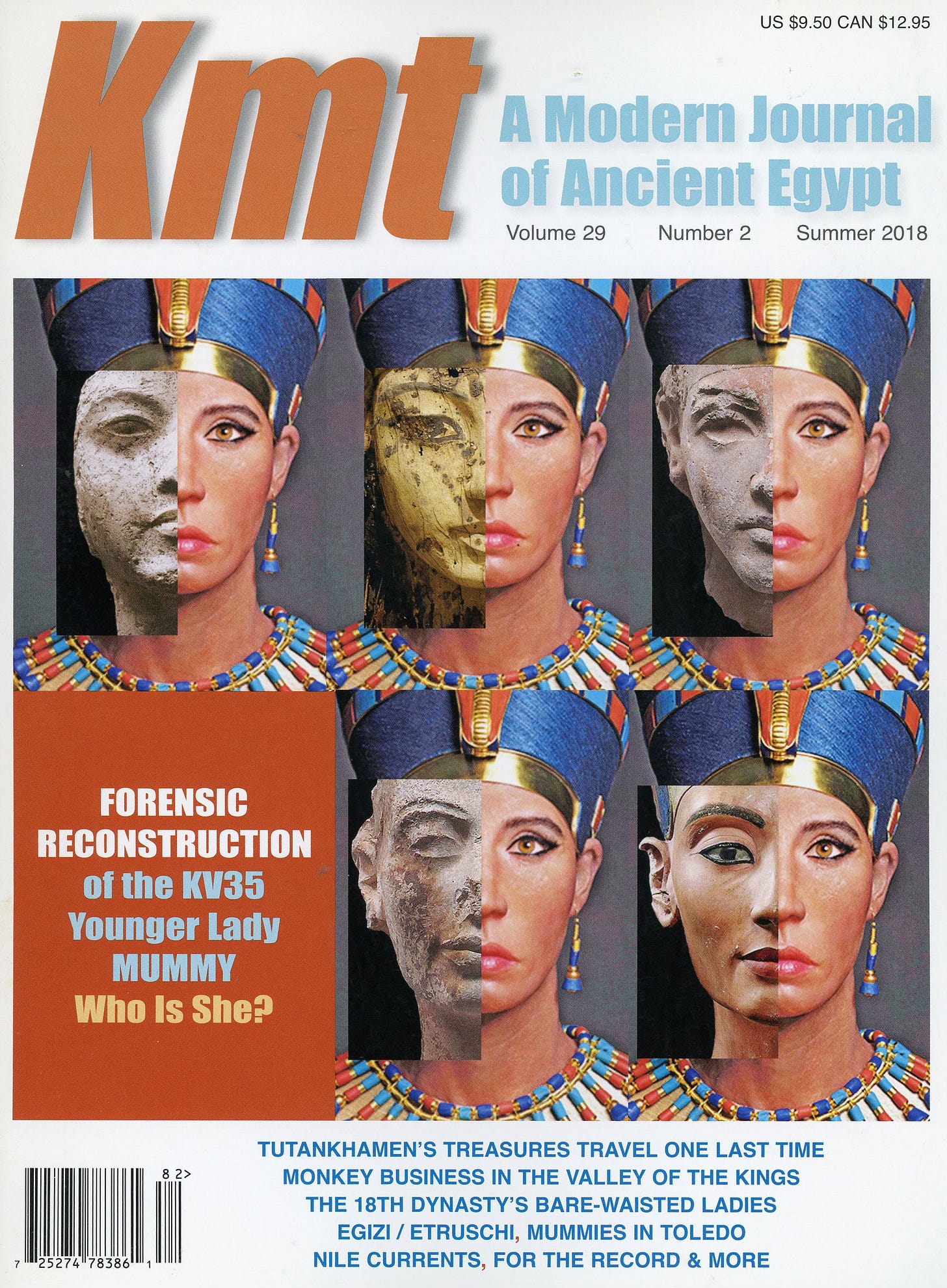

A lifelong artist, Dennis, who turned 84 this year, has not photographed a naked man in 35 years. He spent decades publishing Kmt, a magazine devoted to one of his passions, Egypt, a pursuit he only recently ended after 132 issues, and he has produced several books that chronicle his contributions: his 2006 novel Last Call (begun in 1980 for The Advocate), a book of his beefcake drawings called Blue (2011) and — most indispensable — volumes 1 and 2 of Bare Essentials (from 2021), his phonebook-sized memoirs.

For his first open-ended interview in forever, he spoke to me by phone from his home on a wooded mountainside outside Asheville, North Carolina.

When did you start shooting men?

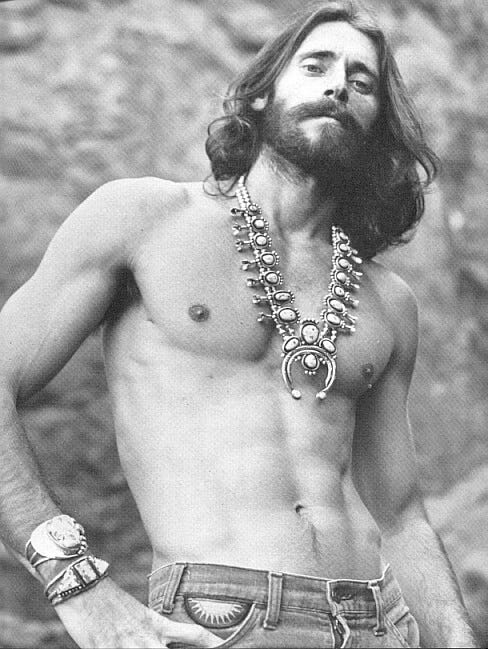

The gay aspect started in 1972, when I moved to San Francisco from Iowa City, Iowa, where I was then director of publications for the University of Iowa. A few months before that long-planned move took place, as a subscriber of After Dark Magazine, I was fascinated by a San Francisco model who'd appeared in a small photo in the magazine's A&E pages named John Appleton, so wrote to editor in chief Bill Como about his interest in me finding Appleton and interviewing and photographing him for the magazine, when I moved to San Francisco in a few weeks. To my surprise Como wrote back, saying that there'd been more response to that small photo than anything else After Dark had published previously, so, yes, go for it! He even included a letter of introduction, so that "if Appleton has any questions about your legitimacy, he can see that I've given you authorization for the interview." So, I did "go for it."

How did you find him?

I began asking around. He wasn’t in the phonebook. People knew him. He was benefiting from his fame from being in After Dark. He had shoulder-length hair and a big handlebar mustache and a fantastic body, all of which were visible in a non-frontal nude photo of him wearing turquoise jewelry by a San Francisco designer friend of his who advertised in After Dark. He was a bartender at the Midnight Sun off of Castro Street. I approached him at work. He was reluctant at first and said he’d been hassled too much and regretted he’d agreed to do the photography in the first place, blah-blah-blah. I said, “Well, here’s my card, and if you ever change your mind, give me a call.” That led to me ultimately doing the interview and the article being published in After Dark.

I’d also begun doing another article on the Renaissance Pleasure Faire. At that time, they were holding one in Los Angeles and one in Northern California over in Marin County annually. In those days, it was a big event where people got dressed up in medieval costumes and strolled around in this farmer’s wooded area with all sorts of vendors. I did photography and I wrote a story about that, which Bill Como published in After Dark. So that was the launching of my journalistic career.

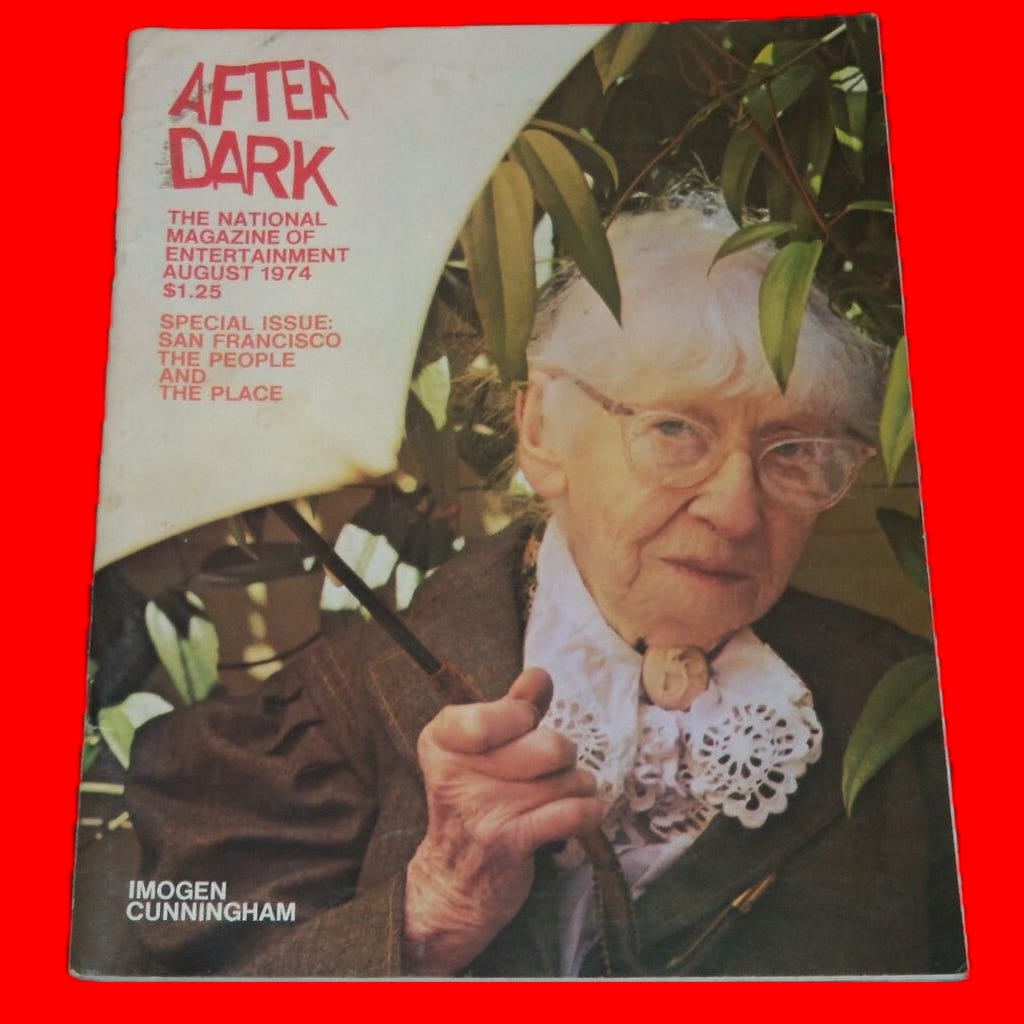

What was After Dark like to work for?

It was a very closeted-gay publication. As I said to Como himself, who came to visit me in San Francisco, “You’re in the closet one issue, you’re out of the closet the next issue. It’s almost like a pendulum. You go so far in publishing a down-to the-pubes male torso, then suddenly it becomes a dance magazine again.” He agreed with me.

We had dinner and he asked if I would be interested in becoming a stringer for the magazine. I didn’t even know what a stringer was. He said he would like to have an every-issue column about the entertainment scene in San Francisco, and so I said, “Well, I guess I can probably do that.” He said, “Well, I can get you free tickets to just about anything. I can give you a press card.” I thought, “Well, I can do that.” Plus, you know, I was paid for the column — I don’t know what, but it wasn’t all that much.

I began doing this column every issue, then Como decided he wanted to do an entire San Francisco issue — August of 1974 — and he gave me the assignment of being the coordinator of pulling that all together, getting other photographers, other writers of the Bay Area, to contribute, and to interview and photograph different entertainment personalities Como thought he wanted to feature in the issue.

I was doing that when I got a phone call from a friend who was the West Coast advertising manager for After Dark. He said he was dog-sick with the flu and had a photo assignment — I didn’t even know he was a photographer at that point — that he was supposed to do that weekend, and he couldn’t possibly manage it, and would I be interested in standing in for him? So ,I said, “Well, what does it involve?” He said, “Well, have you ever heard of Falcon Studios?” I’d heard of them, although at that point in my career I was 32 years old, so I was not exactly a novice, but I hadn't come out until I was 29 and I’d never seen a gay-porn video — or loops, in those days, 8mm. He said he shot production stills for Falcon Studios and I could keep what he was being paid for standing in for him. Voyeuristic me, I said, “That sounds like it might be an interesting experience."

When I went to pick up the check for the work, the owner of Falcon Studios, Chuck Holmes, offered me a job on the spot as his stills photographer, as he'd become dissatisfied with what my friend was doing for him, and he said he was looking for a new stills photographer and he really liked what I’d shot and would I have that interest? I said, “Frankly, I don’t really want to work for a porn company.” He said, “You can do it as a freelancer — you don’t have to be on the payroll.” I said, “Well, then, let’s give it a shot and see what happens.” That led to me not only taking production stills, but also photographing the studio's "instant" stars for promotional purposes, as well as designing Falcon's advertising brochures and print ads. The beefcake photography primarily was for sending shoots of the studio's stars to the Modernismo [Mavety Media] magazines to be published as nude layouts in exchange for full-page ads selling the latest Falcon productions.

How did your work with Holmes unfold?

I labored for Falcon from ’77 through ’80, but then I got disillusioned with the studio's rampant drug scene and the fact that Chuck Holmes was, in his own words “off-planet” most of the time, being heavily into cocaine, and I just finally decided it wasn’t worth the grief that I had to go through on these photo shoots. Falcon's first big production, The Other Side of Aspen, took the crew and models to Lake Tahoe (seen one ski resort, seen them all so Tahoe stood in for Aspen) The week-long shoot was full of mini-disasters, so when we got back to San Francisco, I gave Holmes notice.

However, during those three Falcon years, I'd created a series — “Mags to Match the Movies” — of magazine-format photo books of non-hardcore stills from the films plus nude beefcake of the models, which sold for $8 per copy. Those could be purchased directly from Falcon, but were also available in "dirty" bookstores. They weren't published by Holmes but by Le Salon, a major straight-and-gay porn distributor headquartered in Amsterdam, with a store on Polk Street and a warehouse in the Folsom area. I never got it admitted to, but I strongly suspected they were Mafia-affiliated.

When I left Falcon there were no more "Mags to Match the Movies" from the Studios for Le Salon to publish and distribute. So, soon enough I got a phone call from Larry Nelson — Le Salon's co-owner — saying that he wanted me to come into his office for a meeting and I said, “A meeting about what? I’m not doing any more work for Falcon?” and he said, “Oh, no, no — I have a proposal to make to you.” I went to his office and he proposed that I do magazines for him instead of for Falcon. We negotiated and I thought, “Well, I know how to do it, certainly.” We negotiated a per-magazine deal for camera-ready layouts of softcore beefcake photos, etc. I created Western Man as the publisher of these. Several titles resulted between '80 and '82. I finally was fed up dealing with the Le Salon sleazeballs, when I got an out-of-the-blue phone call from Chuck Holmes begging me to do glamour shoots of several of his superstars for a new Falcon series themed around the fashion-modeling scene, to be titled Style. He said he'd had the models lensed by different Bay Area fashion photographers, but none of them had produced what he wanted, so could I — "please, pretty please" — make it happen for him with my camera? I reluctantly agreed and so was lured back into the Falcon lair.